For a few years, I flogged the proposal to various publishers but many were worried that there were too many people from different backgrounds (e.g. Margaret Atwood sitting alongside Oliver Stone). Another publisher curiously chose to reject it because, to them, it appeared to be a book about me promoting my interviews (as if I was trying to be a low-rent Larry King) rather than seeing it as a commentary on the decade through the eyes of the guests. All told, the book soon faded away and I turned to other projects. However, when recently uncovering the original proposal and sample interviews, I felt that maybe some of them could find a new life on Critics at Large. These pieces are culled from the posts published during this decade.

-- Kevin Courrier, 2017.

In The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, critic Vito Russo examined the way gays and lesbians had been portrayed in the history of American movies. In his book, Russo moves from decade to decade, weaving into his narrative a chronological and thematic awareness of the various representations of gay life; that is, the attitudes that lay hidden and closeted in American culture. He examines with both humour and affectionate insight the early work of 'movie sissies' like actors Eric Blore, Edward Everett Horton and Franklin Pangborn, who gave form to what couldn't be acknowledged openly. Russo shifts from these 'buddy movies' of the Thirties and Forties to contemporary representations which often ranged from predatory and psychotic (Cruising, American Gigolo) to victims (Advise and Consent, The Children's Hour). He even delves into hidden homosexual dynamics not acknowledged such as the unspoken love between Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and Messala (Stephen Boyd) in Ben-Hur (1959), the covert lesbian attraction that Elizabeth Wilson has for Kim Stanley's Marilyn Monroe character in The Goddess (1958), and the originally cut scene between Laurence Olivier and Tony Curtis in Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus (1960), where Olivier's Roman general admits his bi-sexuality to his slave Antoninus (Curtis) whom he's trying to seduce.

The Celluloid Closet was made into a fine documentary in 1995 by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman where they had the benefit of using Russo's book to select clips that supported his thesis. Since this interview with Vito Russo takes place just as the AIDS epidemic was first becoming national news, there isn't the sense of dread here that came to overshadow the rest of the decade. (Although he was a huge activist bringing awareness to the needs of the LGBT community, by the end of the decade, AIDS would also claim Russo himself.) Looking back to 1981, it was a year when dozens of Toronto police officers conducted simultaneous raids on Toronto's most popular bathhouses and arrested more than 300 gay men. Times may have indeed changed since those raids, but maybe certain attitudes haven't.

kc: By concentrating on American films in your book, are you specifically questioning American ideas of sexuality especially where it concerns masculinity and femininity?

vr: Absolutely. Molly Haskell in her book, From Reverence to Rape, said that the big lie about women in media is that women are weak and powerless. I think the big lie about gay people is that such creatures exist only on the fringes of society. They are no part of what we commonly understand as the American Dream. In particular, when I talk about Hollywood films, America is this pioneer country with a masculine pioneer heritage. But I think the movies, of all art-forms, has perpetuated this myth about what is masculine and feminine behaviour to the exclusion of homosexuality. When novels and plays were brought to the screen, homosexual characters were omitted. When biographies of famous people who were gay were made into movies, that person was made heterosexual. And this has never been seen as a serious offence against a person's identity. So the movies have dealt with the subject of homosexuality very gingerly. In the book, what I'm really trying to point out is not so much that homosexuals have been invisible – although they have been in both real life and on the screen – but the willful ways in which the movies have created a world in which homosexuals are really no part of the major culture.

kc: Given the long history of American movies, how did you plan to do this?

vr: Since American movies have provided a falsification of our national heritage, I wanted to write a book about the ways in which homosexuals did appear in the movies. And to show that, in a measure, homosexuals, when they do appear, they appear negatively – and when they appear positively, they are either removed, or deleted, so that the public, both straight and gay, has gotten a false image of who we are. The movies have presented gay culture as pure sexual exploitation where everything gets sexualized. Whereas, heterosexuality has been presented as in all its different facets. You have pictures about heterosexuals who are nasty and those who are nice, but you don't get that with gays. Gay culture is seen as depressing and violent, where gay men are either psychotic (as in Cruising), or sissies; and gay women are predatory, masculine creatures (as in Walk on the Wild Side) who are not really women but pretending to be men. It all gets mixed up with this idea that we have of what is it that a man behaves like? How is a woman supposed to act? I think the movies have hopelessly confused us about these things.

kc: Are you not also addressing the distorted ideas of sexuality that have been perpetrated generally in movies and that has affected all areas of sexual depiction on the screen?

vr: Oh yeah. I think we live in a tremendously sex-negative culture. People do think of sexuality, in general, as being a dirty thing. Whenever you have a movie with heterosexuals that has anything to do with explicit sex, the censors take care of it. With homosexuals, however, we end up defined by sex. It's almost as though a homosexual is nothing else but a person who has sex. Look at how films always show homosexuals in the context of sex, either looking for it, or where sex becomes their downfall. You would never think that these people get up in the morning and go to a job like everybody else. And when you say to people that you want to see more positive portrayals of homosexuals, they can't figure out what you mean.What I mean is simply that if you're going to have a picture that is about something there's no reason in the world why some of the characters shouldn't be gay and some shouldn't be straight. But I don't see Hollywood doing that.

kc: Is that because Hollywood has a long history of creating illusion?

vr: People have asked me: what do you expect of Hollywood? There's no answer to that because Hollywood is, as you said, set up to create illusion. In 1934, when they made Queen Christina, and Greta Garbo played the Queen of Sweden, everybody knew that she was a lesbian. And they knew that Greta Garbo was not going to play her as a lesbian. It's just illusion. That's what Hollywood is about. It's about making a dream for people to believe in. The sad truth is that most people would rather not discuss homosexuality. They would rather not see it. They don't want to know it's there. And the movie industry has done them the favour of creating a world on film in which such things do not intrude on that illusion. That's what The Celluloid Closet is about. It's about the creation of an illusion that had no room for homosexuals.

kc: I know that La Cage aux Folles is not an American film, but don't you think its huge and recent success has marked a change in attitudes that your book is calling for?

vr: La Cage aux Folles is an interesting case because it's the largest grossing foreign film in American history. It's an enormous success. That's why Hollywood is now getting interested in this subject because they see money. La Cage aux Folles does two things: It does not offend most gay people and it makes most straight people comfortable with the homosexual characters in the film. It makes you feel sorry for the characters because they're different, and they're charming. You like them. They're very funny. The actors [Ugo Tognazzi and Michel Serrault] are very, very good. I don't think it's such a great film, but I can see why it's popular. It doesn't challenge anybody's idea of what a homosexual is. People are comfortable with the idea that homosexuals are sort of sissies who are weak and helpless and not threatening anyone. They're never seen having sex. You can't even imagine them having sex. That's also a comfortable illusion. I think if you had made a film in which the characters were not fools and harmless and all that effeminate stuff, and you made them like in [John Schlesinger's] Sunday Bloody Sunday, for instance, with Peter Finch and Murray Head playing two very masculine men who have a love affair – and kiss on the screen – people would go nuts. They don't want to see it. That's the reality of the situation most of the time. La Cage aux Folles resembles some of the Hollywood films of the Thirties and Forties where the sissies, like Eric Blore or Franklin Pangborn, were the comedy entertainment. La Cage aux Folles repeats the success of those movies from the Thirties and updates it.

kc: We used to talk about the idea of mixed marriages on the screen making people uncomfortable. Are we any different here?

vr: The movies have to make people comfortable. It's an audience proposition. Hollywood knows and perceives correctly that the public does not want to see certain things. I actually still don't see white and black mixed marriages in the movies today. After all the discussions of the Sixties, and the Civil Rights movement, and all the marches, and all the protests, audiences still don't want to see a white woman kiss a black man, or a black woman kiss a white man on the screen. They don't want to see it. It still makes them nervous.

During the Eighties, England was going through the trauma of finding itself no longer able to maintain the power and the glory it once possessed when it was an Empire. So, as in the United States, England elected a leader, Margaret Thatcher, who (like Ronald Reagan in the U.S.) promised to restore those "glory days" at any cost. Of course, Reagan and Thatcher, both larger than life figures, ultimately didn't come close to restoring anything glorious. But they did both change the political landscape dramatically. Writers like Alan Sillitoe helped flesh out the past and the present of Britain's years of political turmoil by examining the class conflict that underlined England's despair. When Sillitoe died of cancer at the age of 82, The Guardian wrote that Sillitoe “was part of a generation of working-class writers who shifted the boundaries of taste. Not that Sillitoe, born into the deprived family of a tannery labourer, liked to be defined purely by class. He once said of his 1958 work Saturday Night and Sunday Morning that ‘the greatest inaccuracy was ever to call the book a working-class novel for it is really nothing of the sort. It is simply a novel'.” Part of that modesty towards his work, as well as his thoughts on mortality, made its way into our conversation in 1981.

Vito Russo (1981)

In The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, critic Vito Russo examined the way gays and lesbians had been portrayed in the history of American movies. In his book, Russo moves from decade to decade, weaving into his narrative a chronological and thematic awareness of the various representations of gay life; that is, the attitudes that lay hidden and closeted in American culture. He examines with both humour and affectionate insight the early work of 'movie sissies' like actors Eric Blore, Edward Everett Horton and Franklin Pangborn, who gave form to what couldn't be acknowledged openly. Russo shifts from these 'buddy movies' of the Thirties and Forties to contemporary representations which often ranged from predatory and psychotic (Cruising, American Gigolo) to victims (Advise and Consent, The Children's Hour). He even delves into hidden homosexual dynamics not acknowledged such as the unspoken love between Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and Messala (Stephen Boyd) in Ben-Hur (1959), the covert lesbian attraction that Elizabeth Wilson has for Kim Stanley's Marilyn Monroe character in The Goddess (1958), and the originally cut scene between Laurence Olivier and Tony Curtis in Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus (1960), where Olivier's Roman general admits his bi-sexuality to his slave Antoninus (Curtis) whom he's trying to seduce.

The Celluloid Closet was made into a fine documentary in 1995 by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman where they had the benefit of using Russo's book to select clips that supported his thesis. Since this interview with Vito Russo takes place just as the AIDS epidemic was first becoming national news, there isn't the sense of dread here that came to overshadow the rest of the decade. (Although he was a huge activist bringing awareness to the needs of the LGBT community, by the end of the decade, AIDS would also claim Russo himself.) Looking back to 1981, it was a year when dozens of Toronto police officers conducted simultaneous raids on Toronto's most popular bathhouses and arrested more than 300 gay men. Times may have indeed changed since those raids, but maybe certain attitudes haven't.

kc: By concentrating on American films in your book, are you specifically questioning American ideas of sexuality especially where it concerns masculinity and femininity?

vr: Absolutely. Molly Haskell in her book, From Reverence to Rape, said that the big lie about women in media is that women are weak and powerless. I think the big lie about gay people is that such creatures exist only on the fringes of society. They are no part of what we commonly understand as the American Dream. In particular, when I talk about Hollywood films, America is this pioneer country with a masculine pioneer heritage. But I think the movies, of all art-forms, has perpetuated this myth about what is masculine and feminine behaviour to the exclusion of homosexuality. When novels and plays were brought to the screen, homosexual characters were omitted. When biographies of famous people who were gay were made into movies, that person was made heterosexual. And this has never been seen as a serious offence against a person's identity. So the movies have dealt with the subject of homosexuality very gingerly. In the book, what I'm really trying to point out is not so much that homosexuals have been invisible – although they have been in both real life and on the screen – but the willful ways in which the movies have created a world in which homosexuals are really no part of the major culture.

kc: Given the long history of American movies, how did you plan to do this?

vr: Since American movies have provided a falsification of our national heritage, I wanted to write a book about the ways in which homosexuals did appear in the movies. And to show that, in a measure, homosexuals, when they do appear, they appear negatively – and when they appear positively, they are either removed, or deleted, so that the public, both straight and gay, has gotten a false image of who we are. The movies have presented gay culture as pure sexual exploitation where everything gets sexualized. Whereas, heterosexuality has been presented as in all its different facets. You have pictures about heterosexuals who are nasty and those who are nice, but you don't get that with gays. Gay culture is seen as depressing and violent, where gay men are either psychotic (as in Cruising), or sissies; and gay women are predatory, masculine creatures (as in Walk on the Wild Side) who are not really women but pretending to be men. It all gets mixed up with this idea that we have of what is it that a man behaves like? How is a woman supposed to act? I think the movies have hopelessly confused us about these things.

|

| Al Pacino in Cruising |

kc: Are you not also addressing the distorted ideas of sexuality that have been perpetrated generally in movies and that has affected all areas of sexual depiction on the screen?

vr: Oh yeah. I think we live in a tremendously sex-negative culture. People do think of sexuality, in general, as being a dirty thing. Whenever you have a movie with heterosexuals that has anything to do with explicit sex, the censors take care of it. With homosexuals, however, we end up defined by sex. It's almost as though a homosexual is nothing else but a person who has sex. Look at how films always show homosexuals in the context of sex, either looking for it, or where sex becomes their downfall. You would never think that these people get up in the morning and go to a job like everybody else. And when you say to people that you want to see more positive portrayals of homosexuals, they can't figure out what you mean.What I mean is simply that if you're going to have a picture that is about something there's no reason in the world why some of the characters shouldn't be gay and some shouldn't be straight. But I don't see Hollywood doing that.

|

| Greta Garbo in Queen Christina |

kc: Is that because Hollywood has a long history of creating illusion?

vr: People have asked me: what do you expect of Hollywood? There's no answer to that because Hollywood is, as you said, set up to create illusion. In 1934, when they made Queen Christina, and Greta Garbo played the Queen of Sweden, everybody knew that she was a lesbian. And they knew that Greta Garbo was not going to play her as a lesbian. It's just illusion. That's what Hollywood is about. It's about making a dream for people to believe in. The sad truth is that most people would rather not discuss homosexuality. They would rather not see it. They don't want to know it's there. And the movie industry has done them the favour of creating a world on film in which such things do not intrude on that illusion. That's what The Celluloid Closet is about. It's about the creation of an illusion that had no room for homosexuals.

|

| Ugo Tognazzi and Michel Serrault in La Cage aux Folles (1978) |

kc: I know that La Cage aux Folles is not an American film, but don't you think its huge and recent success has marked a change in attitudes that your book is calling for?

vr: La Cage aux Folles is an interesting case because it's the largest grossing foreign film in American history. It's an enormous success. That's why Hollywood is now getting interested in this subject because they see money. La Cage aux Folles does two things: It does not offend most gay people and it makes most straight people comfortable with the homosexual characters in the film. It makes you feel sorry for the characters because they're different, and they're charming. You like them. They're very funny. The actors [Ugo Tognazzi and Michel Serrault] are very, very good. I don't think it's such a great film, but I can see why it's popular. It doesn't challenge anybody's idea of what a homosexual is. People are comfortable with the idea that homosexuals are sort of sissies who are weak and helpless and not threatening anyone. They're never seen having sex. You can't even imagine them having sex. That's also a comfortable illusion. I think if you had made a film in which the characters were not fools and harmless and all that effeminate stuff, and you made them like in [John Schlesinger's] Sunday Bloody Sunday, for instance, with Peter Finch and Murray Head playing two very masculine men who have a love affair – and kiss on the screen – people would go nuts. They don't want to see it. That's the reality of the situation most of the time. La Cage aux Folles resembles some of the Hollywood films of the Thirties and Forties where the sissies, like Eric Blore or Franklin Pangborn, were the comedy entertainment. La Cage aux Folles repeats the success of those movies from the Thirties and updates it.

kc: We used to talk about the idea of mixed marriages on the screen making people uncomfortable. Are we any different here?

vr: The movies have to make people comfortable. It's an audience proposition. Hollywood knows and perceives correctly that the public does not want to see certain things. I actually still don't see white and black mixed marriages in the movies today. After all the discussions of the Sixties, and the Civil Rights movement, and all the marches, and all the protests, audiences still don't want to see a white woman kiss a black man, or a black woman kiss a white man on the screen. They don't want to see it. It still makes them nervous.

Alan Sillitoe (1981)

During the Eighties, England was going through the trauma of finding itself no longer able to maintain the power and the glory it once possessed when it was an Empire. So, as in the United States, England elected a leader, Margaret Thatcher, who (like Ronald Reagan in the U.S.) promised to restore those "glory days" at any cost. Of course, Reagan and Thatcher, both larger than life figures, ultimately didn't come close to restoring anything glorious. But they did both change the political landscape dramatically. Writers like Alan Sillitoe helped flesh out the past and the present of Britain's years of political turmoil by examining the class conflict that underlined England's despair. When Sillitoe died of cancer at the age of 82, The Guardian wrote that Sillitoe “was part of a generation of working-class writers who shifted the boundaries of taste. Not that Sillitoe, born into the deprived family of a tannery labourer, liked to be defined purely by class. He once said of his 1958 work Saturday Night and Sunday Morning that ‘the greatest inaccuracy was ever to call the book a working-class novel for it is really nothing of the sort. It is simply a novel'.” Part of that modesty towards his work, as well as his thoughts on mortality, made its way into our conversation in 1981.

kc: Considering the acclaim you've received over the years for your novels and their depiction of British working-class life, it's taken you some time to receive recognition for them.

as: That's right. It did take a long time! I started writing when I was about 21, and I didn't get anything published until I was about 30. During that time, I wrote about seven novels and they weren't connected to my early years growing up in Nottingham at all. But all through that period, there was a vein that I was tapping that came through in a number of short stories that were later incorporated into the novel, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. For nine years, I was sending those stories to every English-speaking magazine in the world with the hope of getting them published. But I never succeeded. And yet finally when they were published I felt that they received more praise than they probably deserved. Maybe it was a question of waiting for the time to be right.

kc: That praise though might be based on the authenticity of capturing your own working-class experience. What inspired you to get all this down in writing?

as: When I had to go into the hospital with tuberculosis, it was a catastrophe for a working-class boy. The only thing you really have of marketable value is your strength and your ability to labour. And this was taken from me. When you got told you had tuberculosis in those days it was like being told you had cancer. I mean, 25,000 people a day were dying from it. With those odds, I figured that I was probably going to die anyhow. Then the inactivity – which I couldn't stand – got me reading books and writing. I did that in order to take refuge from the nagging idea that I was finished. One of the first things I wrote about was my experience in Malaya when I was in the Air Force. I was there during the emergency when a communist insurrection failed. But before this time, I had read very little of what could be called mature or adult fiction. So for the next five years, I read every classic in the world and I started writing at the same time.

kc: When you started all this reading, where did you begin?

as: The first things I started reading were the translations from all the Latin and Greek classics. I became familiar with Latin and Greek mythology. I read the Bible inside and out. And then I moved on to the modern stuff. When I was living in Majorca, I had no connection or contact whatsoever with England. So all of my literary and intellectual contacts came from North America or Paris. They would bring the latest magazines and books with them. During the Fifties, I was nurtured on the modern works of Norman Mailer, J.D. Salinger and William Styron. Their work showed me that prose could be vigorous and full of good style. In other words, I realized that one had certain standards to meet. I was also reading a lot of Yiddish writers who wrote about living in a schtetel in Eastern Europe during the 19th and early 20th Century. That writing had a quality of tenacity and richness. If you were to amalgamate all of these influences, they'd connect very much to the first eighteen years of my life. So I was inspired by that amalgamation to keep on writing those stories which subsequently published and which I still write today.

kc: It seems that the imminent thoughts of possible death forced you to come to certain insights.

as: Well, it's like Dr. Johnson who said, "There's nothing that collects a man's mind more than the thought that he's going to be hanged in the morning." The poet Robert Graves, in Majorca, told me that it's useful for every poet if once in his life he dies. Graves had died on the battlefield and was brought back to life by pure chance. I considered that I had died when I was told I had tuberculosis. But then I was reborn in a sense. And being alone – spiritually, that is – in a hospital room was very good, as you surmised. When I got out of the hospital, it was continued by an exile. Every since I was young, I wanted to get out of England. Something about it made me feel that I loved it too much, or I couldn't stand it. So after having been in Malaya for two years, I had the pension from the TB. With that, I went to Spain and France so I could write about England. I had to be away from it - like looking through the wrong end of the binoculars – in order to understand it. Out of this, while sitting under an orange tree, I wrote Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. That was the best thing I could have done to get it right.

kc: How much perspective did having that distance give you on England?

as: You see, before the age of eighteen, I knew nothing about the English class system. There was nobody to tell me about it. If someone had told me that I was working-class, I would have told them to get lost. I didn't want to know about such things because I believed that everyone was an individual, or at least, an independent person. Simply, I wanted to distance myself from the idea of class. As a writer, if you get entangled with the class system and wonder where you fit in, it can ruin you. I just wanted to get out of it. And by going to Spain and France, I never had anything to do with this question. Living abroad on a pension, you became an exile and a traveler. You are pulled into your own psyche. So I came back to England when I was thirty. And I was completely formed. I still had nothing to do with the class system and that's what was really important to me.

kc: Wouldn't you say that view is shared by Colin Smith in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner? He doesn't fit into any class system, or want to be part of the working-class. He exists in the underground and is against all values, very much like the Dostoevsky protagonist in Notes From the Underground. Did you identify strongly with Colin?

as: I think The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner came from a very deep part of myself. Even though it is set in Borstal, you could say it's about a writer. But, of course, I put it into a different context since you shouldn't write a story about another writer. That's banal. A writer is an individual and shouldn't align himself with any class to the extent that his commitment to that class becomes political. I know it's difficult to avoid this altogether, but you must maintain an objectivity and an independence. You have to stand on the outside and then, as I discovered writing Saturday Night and Sunday Morning from Majorca, maybe you can depict it with more reality, more truth, and if you're lucky, more profundity.

kc: Recently at a party, someone suggested to me that when England lost its colonies, it ceased to be.

as: Well, in those days when England had an empire, the working-classes didn't benefit very much. In fact, they were in a desperate plight. But it had a purpose in those days because if the working people became restless at home, they could always have their energies channeled by going out to the colonies. All the excess energy could be tapped off, where today it's getting all bottled up at home. Therefore, we're getting more trouble now. It's a serious situation and the most important thing in the long term is to inculcate a way of showing people how to use their leisure time. Technology has now grown to the point where there are going to be less and less jobs in the future. More jobs will be done by automation. And I don't know, but perhaps it will be a good thing when people have less work because they will have more time to do things that are intellectually stimulating. But I also believe we have more tribulation to come before we reach that kind of enlightened period.

D.M.Thomas (1981)

The conventional biography was subverted in different ways during the Eighties. Wallace Shawn, for example, with playwright Andre Gregory and film director Louis Malle concocted My Dinner with Andre (1982), a film about two men having dinner and discussing philosophical issues set in the dramatic context of a performance piece. Author David Young, in his book Incognito (1982), stumbled upon a box of old photographs that he found in an attic of an old house he purchased. He decided to write a fictional biography based upon the sequence of photos he discovered. Thriller writer William Diehl (Sharky's Machine, Chameleon), a committed pacifist, wrote lurid pulp as a means to exorcise the violence within himself. What many of these artists in the Eighties were attempting to do was to link to their work to a larger collective memory; a shared mythology enhanced by an expansive popular culture.

In 1981, poet and novelist D.M. Thomas worked with historical fact to create a vivid and powerful work of fiction that would link the psychological insights emerging in the work of Sigmund Freud with the terror of the Holocaust during WW II. He did it in a novel called The White Hotel. The White Hotel was broken into three movements opening with the erotic fantasies of Lisa, one of Freud's patients, which overlapped with the convulsions of the early part of the 20th century leading to the Holocaust. Over the years, many film directors including Terrence Malick (The New World, Tree of Life), Bernardo Bertolucci, David Lynch (even Barbara Streisand) have attempted to put The White Hotel on the screen. But its dreamy horror has yet to be fully conceived as cinema. In one of my first professional radio interviews at CJRT-FM, D.M. Thomas explained how he created such a potent fiction out of this unsettling reality.

kc: Why did the fusion of Freud and the Holocaust become the central motif in The White Hotel?

dmt: There are these powerful events of the 20th Century: Freud's discovery of the unconscious, his marvelous case studies of individuals, and the way he mapped out this mythic territory of the mind; and there are those horrific historic events like the Russian Terror and the Holocaust. No one has thought of associating these events before but the idea for The White Hotel clicked when I saw a connection between them. I made the connection between a patient of Freud having some terrible hysterical symptom stemming from a traumatic event and something like Babi Yar, itself being a hysterical outburst based on anti-Semitic feelings. It seems to be that there is always a struggle – both personally and socially – between the death instinct and the life instinct, as Freud discovered. The contrast of the individual and the historic is the key to the book.

kc: You also create a link between the psyche of the character Lisa and her premonition of the historical events to come – Why make this link?

dmt: Well, Lisa, who is Freud's patient, does possibly have these hysterical symptoms not only from what happens in her childhood but also as a premonition of what is to come, which is the Jewish experience. It seemed to me that any sensitive person of the Jewish race being around in 1920 would have felt the future looming. They must have had intuitions because there was anti-Semitism already. It didn't seem unlikely for someone this sensitive to have those premonitions since you can find a mixture of hysterics and sensitivity going back to the Delphic Oracle or Cassandra.

|

| Sigmund Freud |

kc: Why does history play such a dominant role in your writing?

dmt: Certain events just keep haunting me particularly the history of our own time. I think that the period of the thirties and forties were the most terrible in human history. Both Hitlerism and Stalinism were horrific things. Then after that we get Hiroshima. Anyone who was born during that time, as I was in 1935, is touched by the consciousness of those events even though those events didn't touch me personally. I'm a child of Babi Yar as much as anyone else. So my mind keeps coming back to these events, but I always try to relate it to individual lives because that's what interests me as a writer.

kc: How does your understanding of Freud though add to your understanding of human history and its impact on the individual?

dmt: I feel that Freud didn't take away dignity from human beings as some people claim. He gave us dignity back. Humanity was being reduced by the scientific studies of Darwinism and by doubts about religion. Freud saw in our minds a great battlefield between powerful forces. The Oedipus conflict is in itself an epic struggle of the child against the father. It doesn't matter if it's true. I don't know if I even have an Oedipus conflict. But it's a poetic drama unfolding. And basically what I like about Freud is that he was a poet more than he was a scientist. When the idea for The White Hotel came, it suddenly struck me that I could include a Freudian case study. And I enjoyed feeling my way into his mind and writing in that very dry and passionate style.

kc: Do your own dreams and fantasies have any bearing on the way you write about events like the ones cited in The White Hotel?

dmt: Not generally because one's dreams are usually only of interest to oneself. I do create waking dreams. Sometimes the poems I write are from dreams, but not in The White Hotel. I have used my fantasies, however. My own inner life I do draw upon.

kc: Maybe what I'm after here is whether or not that consciousness of the Holocaust is being worked out in your writing by exploring its very influence on the characters.

dmt: I suppose it is a way of exploration. One of my books of poetry is called Love and Other Deaths. All of my writing is about those two forces: love and death. I know they're very present in me, so The White Hotel is also an exploration of my own psyche. It grows out of me and somehow turns into Lisa. I explore even though I haven't yet found the answer.

|

| White Hotel painting |

kc: Whether you've found the answer or not, The White Hotel has certainly touched a nerve in the public. Did you anticipate any of this controversy?

dmt: I think I was tackling dangerous territory. The Holocaust is very difficult to deal with and then you have the sexuality in the book which is the meaning of The White Hotel. It goes from a very personal and subjective study of the sexuality of a woman to then seeing her as an anonymous number in the mass of those wiped out. It was deliberate. But some people found that offensive and shocking. There are terrific polarities of feeling about this book which is disturbing in itself. It's a bit like having a perpetual suite in The White Hotel (laughs). There's been lots of milk and honey as well, like traveling to places I might not have gone to and where responses have been nice. Then there has been the bad side of being under the pressure of becoming so suddenly exposed and naked with people looking at me. Like The White Hotel, it's very interesting, but not very restful.

kc: Don't those intense reactions from readers go with the territory of using your imagination to make connections between people and their culture, or even between people and their understanding of sexuality?

dmt: I think so. Robert Frost once said that the writer has the freedom to fly off in wild connections. And that's the greatest freedom of all, to be able to leap from one image to another connecting metaphor that might be light years away. This is marvelous because you can do it whether you are in Britain, Canada, or the Soviet Union. And maybe it comes easier in a State where there is great oppression because you always get thrown back on your imagination. This is probably why Russia has produced greater artists than in the West in the last fifty or seventy years. Oppression forces you to be subtle. You have to make your point in invisible ink. That's often more effective.

John Cage (1982)

By the Eighties, contemporary composers like Philip Glass and R. Murray Schafer were now having their music felt in pop circles. John Cage was perhaps the most influential of those avant-garde composers who helped make that possible. He had a huge impact – both artistically and philosophically – on popular music (including Frank Zappa, Cabaret Voltaire, Yoko Ono and Brian Eno). Born in Los Angeles in 1912, Cage studied music with serialist composer Arnold Schoenberg and later with Henry Cowell to develop the notion of aleatoric music (or chance compositions), such as 4'33", where a pianist sits at the piano for that length of time without playing while allowing the ambient sound to form the basis of the composition. He also wrote piano pieces where the piano strings themselves would be "prepared" with applied wood blocks, or screws, to change the timbre of the work. In short, Cage made us aware of the role of sound in the conception of a composition.

When I spoke to Cage in 1982, he was in Toronto to perform a relatively new work at Convocation Hall called Roaratorio (1979), a work of ambient surround sound recorded in the streets of Dublin and played through multiple speakers while he read from James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake. The Eighties would be his last decade with us (he died in 1992) and in this interview he seemed to be in the process of summing up his work.

kc: How influential do you feel you've been on popular music?

jc: I don't like the notion of influence. Let's say someone is struck by something I've done, or something that someone else has done, then if he really does something that is lively himself, he'll have to translate that thing into his language. In that way, it'll come out true. You can't just be influenced. A person has to grow it in themselves.

kc: So a person has to open a different door for themselves much like you did when you decided to tamper with the piano?

jc: That's right. Just like my teacher Henry Cowell did before me. I frequently held the piano pedal down while Henry would run behind and play his banshee. I also once saw him use a darning needle on the bass strings of the piano to get a glissandi of overtones. So it was perfectly reasonable for me, after he opened that door, to put screws and weather stripping between the piano strings. The only change was that all the things that Henry did were mobile on the strings. For me, the main characteristic of the prepared piano was that they're stuck to the strings (laughs). And by the last work that I did for prepared piano, those pieces that had time length by title were grouped by the different objects I inserted – like wood blocks. That way, the preparation was in constant transformation.

|

| John Cage in concert |

kc: This is one of the areas that fascinates me about your music. You not only see music as an evolution of technique, but also an evolution of our ability to accept different kinds of sounds as part of the music composition.

jc: You see, I was well aware early in my life, after I studied two years with Arnold Schoenberg, that I had no feeling for harmony. He was aware of this, too. And he told me that I would never be able to compose. I asked him why and he said that I would come to a wall that I could never get through. Now two years before I studied with him, I had promised to devote my life to music and composing. Since I felt obliged to continue, I figured that I would just have to hit my head against that wall (laughs). And what I think I've done in my work is to show alternatives to tonality and harmony as the structural means of music.

kc: What kinds of alternatives did you discover?

jc: On the one hand, the alternatives I discovered opened the doors to noise which tonality doesn't do. And the way it does this is by taking time as the basis of composition thereby replacing pitches and tonality and harmony. And time is hospitable to everything, whether it's musical, or not musical. So I would say that if you can hear something, it's natural for music.

|

| Arnold Schoenberg |

kc: That would include hearing a pin drop, or someone coughing at a concert...

jc: Well, in New York, we now have concert halls where you can hear trucks passing by outside unlike others where formerly they made the architecture so you couldn't. Maybe the first music place where you heard extraneous noises was the Museum of Modern Art where you could always hear the subway going underneath (laughs).

kc: Many have claimed that you caused an upheaval in music with the prepared piano and your aleatoric pieces that were right in tune with the musical upheavals of the previous century when Schoenberg and the serialists challenged the excesses of Romanticism. True?

jc: What happened in Europe musically around the turn of the [20th] century was that you had the emergence of both Stravinsky and Schoenberg – not to mention Bartok. And music then divided itself into streams. What I chose was the stream of Schoenberg because his notion of the twelve-tones struck me as an open sesame. I got the notion that the twelve-tones were equal in importance to having just one tonal center. And I preferred that to the notion of major and minor scales where one tone is more important than all the others. I took that notion of equality and extended it to the world of noise and all sound.

|

| Christian Wolff, Earle Brown, John Cage, Morton Feldman. |

kc: Wasn't there a group of you that worked together reshaping music in this manner?

jc: Yes. It was much later in New York. There was Morton Feldman, David Tudor, Christian Wolff, Earle Brown and myself. And we saw many possibilities. It was Feldman who created music on graph paper that listed the number of tones to be sounded. That was the first piece composed with the intention of being genuinely indeterminate. I found it very inspiring to a great deal of my work.

kc: What kind of audience did you originally attract to your music?

jc: Suitably, it wasn't other musicians, but painters. You see, the upheaval in painting had already taken place, so that they welcomed this upheaval in music. We never had large audiences – maybe 120 people could be counted on to come to one of our concerts – but they were all visual artists. There were only a few exceptions. Henry Cowell, of course, and also [the electronic music composer] Edgard Varèse.

kc: You might not want to think of the influence that you have on contemporary composers, but it still exists. How could we think of Brian Eno and his ambient music without what the group of you did?

jc: Yes. But what would the group of us have done without the furniture music of Erik Satie? He thought of music that should be in the environment and which could be ignored. Of course, no one ignored it (laughs). He did at least suggest that we could.

|

| Erik Satie |

kc: Are we to expect then that musical standards are always being created to be broken down?

jc: When we least expect it, a new idea will come to us. We seem to be surrounded by possibilities that get into our awareness and we act upon them. It happens when you least expect it. I remember a book by Alan Watts. He wrote a great deal on Zen Buddhism. In one book, he put a bunch of scrambled letters on a page and suggested to the reader that we try to figure it out. What did those letters mean? Naturally, you couldn't figure it out if you tried, but if you forgot about it, the answer would come to you. The mind can block us from doing the next thing that we don't yet know. It does it by the means of our memory and our tastes. So if we can free ourselves, as Duchamps once put it, by reaching the impossibility of transferring from one image to the like image – from one Coca-Cola bottle to the other – by eliminating our memory imprint of the former image, each Coca-Cola bottle will be new to us. And from a Buddhist point of view, each one would be at the center of the universe. But also at a different center because the light doesn't fall on two Coca-Cola bottles in the same way. Therefore, they do look different.

kc: I see. It's just like Schoenberg's twelve-tones where there's no tonal center.

jc: That's right. There's a multiplicity of centers. At least, that's the view I find most refreshing.

kc: What has been the greatest benefit for you by opening up the world of music to noise?

jc: My own experience, now having opened the doors to that music, is that I really enjoy the noise –almost more than any music. It's sufficient for me.

kc: Do you think that even now at 70 years of age there are still new areas of music for you to tap into?

jc: I'm sure that not only that there are, but there always will be. I really don't think we'll come to the end (laughs). Life consists, for many people, of opening doors. Perhaps there are some people who prefer to have them shut, but I'm not one of those. I like to open a door. And if I don't do it today, I hope to do it tomorrow.

William Diehl (1982)

The interview with author William Diehl (Sharky's Machine, Chameleon, Primal Fear), a writer who wrote luridly powerful pulp with a political tinge, became a fascinating exercise in self-examination. When I discovered that Diehl was a pacifist who once marched with Martin Luther King in the South during the demonstrations against segregation, I was compelled to find out how such a peaceful man reconciled his polar opposite. To both my surprise and satisfaction, he was more than happy to comply while providing a vivid examination (through his thriller Chameleon) of the growing political mercenary movements in the Eighties that would ultimately lead to Waco and Oklahoma City. Diehl would die at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta on November 24, 2006, of an aortic aneurysm. At the time of his death, he was working on his tenth novel.

kc: I get the impression that when you sit down to write there's quite a war going on in your head.

wd: That's quite true. I find that subconsciously things from my past keep getting in and coming out of the books. A lot of the critics in reviewing Chameleon have called it one of the most violent books ever written. Yet I'm basically a pacifist. I don't own weapons. I don't even have a gun in the house. I live alone on an island. No doubt that it's a throwback to World War II when I served as a ball-turret gunner. All of those latent aggressions and violence are surfacing now. It has to be that because I'm certainly not interested in becoming active in the things I write about. But I should say that there's nothing about the violence and the weaponry that I depict in Chameleon that isn't really happening today.

kc: In this book, you examine an assassination squad – a secret terrorist organization that trains at "The Farm" – What is that?

wd: I knew that "The Farm" existed. I've known about it for several years and I met the man who runs it. He's a guy named Mitch Warbell. One night, we started talking about the place and he told me that while a lot of mercenaries go through the training course, many of these people are bankers and folks going to countries where terrorism is prevalent. They take the course as a self-protective device. That's what triggered the idea. Then I went out and took the course. Over a period of six months, I spent time talking to the instructors. Their stories gave me the basis for the book.

kc: When you were describing a moment ago those latent aggressions and the violence, how does it manifest itself when you are writing a book like Chameleon?

wd: The first chapter of the book was triggered by the Doobie Brothers' song "What a Fool Believes," which I heard on the radio as I was driving home. The song started a lovely little romantic story going in my head. Suddenly, it turned very dangerous and it got very violent. I don't know where it came from. All of a sudden, as I'm working on this romantic idyll, it got very tough. It was then that the story took off.

kc: At the heart of this violent story is a particular code of honour. Where does this come from?

wd: Chameleon is a story about honourable people versus dishonourable people. And I've put at the heart of it the Oriental philosophy of honour. My belief is that the Oriental philosophy of honour is a very positive and uncompromising belief. Whereas in my country, you have to struggle just to be a little bit honest. That's why in my novel Sharky's Machine you have four cops who are basically losers who become winners in the end because they couldn't be corrupted. That's also the story of Chameleon where you have two or three people who are honourable. I'm dealing with knights on white horses slaying dragons. And I still believe that's possible.

kc: Does the writing of action fiction though become a safety valve for your own violent fantasies?

wd: It's indeed a great release. What it is, is playing out your fantasies on paper. For instance, in Chameleon, I developed my own brand of martial arts. What I did was draw stick figures where I could try out the moves – sometimes in front of a video camera – and describe them. I really got into it. Then I also got into the method of trying to remember things without taking notes which is what these people in the book could do. I never took it as far as them but I found that if I went into a restaurant and found it fascinating enough to use in a book, I can remember every little detail of it. Then I file it away in my word processor. Often I tell people that I'm a method writer because I actually act things out in the room because you deal with your psyche on paper.

kc: How do you act these things out?

wd: If I'm angry, I go in and write a violent passage for a book. When I come out, I don't even want to step on an ant. If I'm writing about a character that I really like, and I know that the character is going to be killed, I can get depressed for a couple of days. In Sharky's Machine, when Nosh, Sharky's best friend, gets killed, I got into a funk over that and I couldn't write for over three days. I was so upset over having to kill that character. When certain things happen, I react emotionally as it is really happening. It can be draining at times. It's a good thing that I live on an island where my house is a hundred feet from the Atlantic Ocean. A lot of times after writing a passage I'll go down to the beach just to calm myself down. What happens is that I get hysterical inside and I can't translate that on paper. How do you describe to anybody the feelings and thoughts that go through your head at times like that? The best thing to do is find a way to get rid of it, once you've used up the part you need to put on paper.

kc: I'd like to take that a step further. If you resolve certain conflicts within yourself, does it also mean that your writing will change?

wd: Absolutely. My writing changed radically from Sharky's Machine to Chameleon. And a lot of it is in the emotional content of the book. I think Chameleon is a better book than Sharky even though it feels colder. Maybe that's because of what some of the characters do in the story.

kc: Has living on the beach provided the sanctuary needed?

wd: Yeah. I remember when the film of Sharky's Machine had its world premiere in Atlanta. All of the movie stars came and it seemed like the biggest thing since Gone With the Wind. As a result of it, I started to get a celebrity status in Atlanta. I was expected to be places and doing things. This started to really disturb me because I started to lose the independence that I had gained by writing these books. One day, I got on this airplane and flew down to the coast of Georgia and told this real estate agent that I wanted an island. The agent found me one immediately. Now I don't even go to the mainland. I don't even want to leave this place. There's one place there that is like Cannery Row restaurant filled with expatriates and people who just go to escape like me. I go there in the morning, read the newspaper and chat, then I don't see them until the next day. Since I moved there my writing productivity just jumped.

kc: I guess the biggest distinction some would have to make meeting you – or knowing you – is to separate the man from the writer?

wd: Probably most writers become very involuted and difficult to deal with when they're working. And I feel that I'm difficult to deal with because I vague-out. I can hold a conversation without even knowing what I'm saying. I'm so used to doing it. When I'm through, I wake up one morning and the book is finished and I have nothing to do. It's a bit of a downer because I've been living with it for so long. Then I go and do crazy things like scuba diving for weeks at a time. It's a schizophrenic way to make a living, but I wouldn't have it any other way. I love the isolation. Nobody can invade it. What other occupation is there where you can be totally isolated and deal with yourself in whatever terms you want to deal with yourself in?

Allen Ginsberg (1982)

My thinking was (and still is) that it’s difficult taking into consideration the political landscape of the Eighties without examining aspects of the Sixties. Many ghosts from that period (i.e. Vietnam, the Cold War, civil rights) continued to linger as unresolved arguments that underscored political and cultural actions in the eighties. If cynicism became more the common coin twenty years after the idealism sparked by JFK’s 1960 Inaugural address, some voices including poet Allen Ginsberg was set out to uncover what the political lessons of the Sixties were. While historically Ginsberg had emerged as part of a group of writers and artists in the early Fifties tagged by the media as The Beat Generation, his voice continued to be a large part of the Sixties counter-culture (a voice that continued to loom large until his death in 1997). As part of this collection of American post-World War Two non-conformists, such as William Burroughs (Naked Lunch), Jack Kerouac (On the Road) and Gregory Corso (The Vestal Lady on Brattle), Ginsberg rejected materialism and embraced new forms of expression partly inspired by William Blake and Walt Whitman. This involved an interest in Eastern religion, alternate forms of sexuality, and experimentation with drugs. Most famously known for his epic 1955 poem "Howl" ("I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix.") in which he celebrated the hedonism of his generation while denouncing the destructive forces of American capitalism, Ginsberg also became a champion of anti-censorship after "Howl" became part of a famous obscenity trial in 1957 (documented in the 2010 film Howl). Eventually, Judge Clayton W. Horn declared that "Howl" was not obscene while adding, "Would there be any freedom of press or speech if one must reduce his vocabulary to vapid innocuous euphemisms?"

Throughout the Sixties, Ginsberg (who was a practicing Buddhist) continued to write and perform and was highly active in the political unrest of the period. When I met him in 1982, he was in Toronto to give a reading and perform some songs he wrote with the local punk band, The Diodes. He was also promoting a book that addressed the demise of the underground press, once again speaking out against censorship. As he walked into the studio, dressed sharply in a custom made suit and tie, he didn't look like the bearded, long-haired bard who once confronted an army troop train of soldiers bound for Vietnam with chants of "Hare Krishna!" At which point, with cultural change in mind, the interview began.

kc: Some of the key figures of the Sixties in recent years have either died, faded away, or become born again like Bob Dylan, or...

ag: Many of the pop figures have. But not the literary figures! The literary figures, in fact, have grown in power. William Burroughs has just finished a best seller called Cities of the Red Night which I think is one of his best books. Gregory Corso, another of the so-called Beat Generation, has just published a fascinating new book of poetry.

kc: So you're saying people haven't disappeared at all.

ag: Oh no. That's just cornball mythology. Kerouac is dead. Neal Cassady is dead. Yet there are endless numbers of great poets still teaching, writing and becoming more mature and powerful. That's how it should be. Most artists ripen and get stronger if they're real artists and have a true fix on life and death in eternity.

kc: Most people today though continue to believe that the counter-culture of the Sixties died out by the Seventies.

ag: Yeah. But you could equally say that the United States died out as well. It's still in its death throes, too, with the current war in El Salvador and the paranoiac Cold War policies of Reagan which are ruining the nation and bankrupting it.

kc: But why do you think those policies have grown more popular today?

ag: I don't think they have. Those views are very much bought and paid for by the multi-nationals. There was a story in the New York Times in 1979 by David Burnham accounting for the PR campaign of the nuclear industry. He said that nuclear groups like Exxon spent $470 million for public relations and propaganda, advertising and brain-washing, while only $4 million was spent by anti-nuclear activists Ralph Nader and Helen Caldicott. So it's a bought consciousness that the media has unfortunately co-operated with.

kc: How do you account for this kind of national sleepwalking then?

ag: America is so egotistic. It's so insistent on being Number One. I mean, if a guy in a bar went around saying that he was Number One, he could beat up anyone, he was stronger than anybody, more important than anybody, and wanted to run the bar, everybody would shrink away realizing that they were dealing with a big neurotic. It's even worse when he's drunk on a $170 billion budget.

kc: If American culture has changed so dramatically since the Sixties, what kind of view does the media today have of the literary movement you were part of?

ag: There's a certain stereotyping in newspapers. I don't know whether it's dumbness or the lowest common denominator, but they're not so interested in good news. They're certainly no longer interested in the continuity of art. They're now interested in the superficial giggle. I just went to a radio program where the fellow interviewing me asked how I'd changed and why I was wearing a suit and tie – as if it were some awful betrayal of beatnik beard! There was no inquiry as to the gentleness at the base of the literary movement that was called the Beat Generation.

kc: But does the Beat Generation still even exist?

ag: It still exists – nameless – but probably more influential than before.

|

| poet Allen Ginsberg chanting in the Sixties |

kc: Is it really important that it has a name?

ag: No. It was invented by newspapers to begin with. So it was their poem and nobody wants to write their poem necessarily. We all did our best to make sure their poem was a good one though.

kc: Besides the perceived disappearance of many Sixties figures into obscurity, one thing that did literally disappear was the underground press. When did you begin to get concerned for its survival?

ag: I was very much concerned in the late Sixties and early Seventies with the future of the underground press. That's a big part of why I'm now visiting Toronto. I'm attending the Amnesty International convocation where I'm presenting a report from PEN (ed. an independent, non-profit organization that is committed to defending freedom of opinion). We found that there was a concerted attack on the underground press in the United States by the FBI, in co-operation with the CIA. The attack took the form of the burning and bombings of underground newspaper offices. There was constant harassment of vendors, distributors, and printers, and banning from college campuses. There were also phony drug busts by agents planting marijuana as a way to bust the office and seize all the records and mailing lists, and smashing the typewriters and typesetting machinery.

kc: How deeply entrenched were the police in this sabotage?

ag: There were police spies constantly. They were always spreading disinformation. If there was going to be a peace march, the spy would call in and report that it was happening at a different time, and in a different place. There were anonymous letters sent from a "concerned taxpayer," or a "concerned citizen" – or even better – a "concerned student." The Great Speckled Bird, an underground newspaper in Atlanta, was put on trial for obscenity. They won the case but it drained the paper of money because they were operating on a shoestring. The FBI also had landlords raise the rent for these places by telling them that subversives lived and worked there. It was a great network of conspiracy which reduced the number of underground publications from 400 in 1968 to 60 in 1975.

kc: How long did it take you to accumulate all of this information?

ag: Twelve years. All of this information comes from the files of the FBI and your own RCMP who was doing the same things here as in the States. When I started investigating this, as I said, back in 1968, the mainstream media said I was paranoid because that sort of thing didn't happen in America. And they kept that line until they started getting harassed by Spiro Agnew. The underground press was more vulnerable though. So all of this information was collected and, with the help of PEN, put into a book called Un-American Activities: The Campaign Against the Underground Press.

kc: Besides the obvious reason for having this knowledge available, what do you think this book could do for those wishing to understand the counter-culture that was at work during the Sixties?

ag: It would be very useful for younger people of this new wave generation who wonder why the Sixties radical consciousness movement seemed to diminish as you suggested earlier. It would be important for them to realize that it was a concerted effort of the government to squash the movement because the government found the counter-culture interesting and important. It was so important that they spent millions of dollars to sabotage the counter-culture intellectual news organs. This book is for those who have yet to realize that if you don't know your history, you're doomed to repeat it.

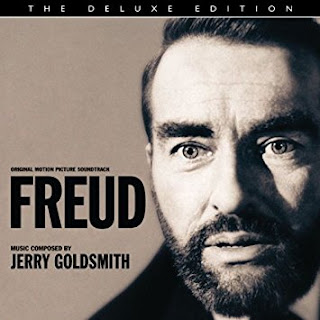

Jerry Goldsmith (1982)

Where the original Hollywood composers who pioneered film music, such as Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann and Alex North, either came from classical music backgrounds, or continued to do concert work while plying a trade scoring movies, Jerry Goldsmith always wanted to be a film composer. Born in 1929 in Los Angeles, he studied piano at six and by the time he was thirteen began having private lessons with the legendary concert pianist Jakob Gimpel. While studying counterpoint and theory with the Italian composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (who also tutored Henry Mancini and John Williams), Goldsmith happened to see Hitchcock's Spellbound which was scored by Miklós Rózsa and he was hooked. Goldsmith would soon enrol and attend lectures Rózsa gave at the University of Southern California until he began more practical studies in scoring at Los Angeles City College. By the Fifties, Jerry Goldsmith began work in radio and later scored live CBS television shows such as Climax!and Playhouse 90. Soon he was scoring multiple episodes of Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. In 1961, composer Alfred Newman became deeply impressed with Goldsmith's work on Thriller and recommended him to Universal Pictures who needed a composer for their new modern western Lonely are the Brave (1962). From there Goldsmith mapped out a career that spanned over 40 years.

When I spoke to Jerry Goldsmith in 1982, he had just finished scoring the Tobe Hooper/Steven Spielberg horror thriller Poltergeist and was in Toronto to speak at a Film Music Symposium. At one point in the interview, we started discussing his thoughts on a variety of pictures and that section is what's included below.

kc: Your music for John Huston's Freud is one of my favourite scores. How did you come to work on that picture.

jg: It wasn't easy. I'd done this picture at Universal called Lonely are the Brave with Kirk Douglas, the first major feature film that I'd scored. My work on that project was largely due to the insistence of pressure by Alfred Newman who was a huge fancier of my music. Universal was so pleased with my work on that picture that their musical director Joseph Gershenson continually urged John Huston to have me do the picture. I was very keen to do it because it was one of the most talked about movies about to come out. So when I got it, it turned out to be a big breakthrough for me after six months of pressure on Huston.

kc: Did you find Huston musically sensitive to your ideas?

jg: Yes and no. But I learned a great deal working with him. One of the most important things John taught me was during the time we were spending hours spotting music for the picture. One scene in particular took three days to figure out. There wasn't even that much music in the film, or very much in the way of dialogue either. So I didn't want to force music into the story. But we went back and forth as to whether we should put music there, or shouldn't we put music there, and John kept leaning towards including it and I kept leaning away from using music. At one point, he finally told me, "If you don't feel it, then don't waste your time trying to write something you don't feel. It won't work." That's something I've never forgotten. When I get into another situation like that with another director, I always tell them what Huston told me – and he was sure right. That settles the discussion.

kc: If Freud showed your imagination at work learning how to spot music in a movie, A Patch of Blue reveals something of your delicacy as a writer.

jg: A Patch of Blue, a movie about a man (Sidney Poitier) who falls in love with a blind woman (Elizabeth Hartman), was that kind of delicate and sensitive picture. It's also the kind of film that I prefer to do. People don't tend to remember that I can do those things. They concentrate more on the big epic movies and I have to remind them of the little ones like A Patch of Blue and Lillies of the Field.

kc: Why are these smaller dramas so much more satisfying for you?

jg: I prefer the kind of dramatic situation where there is someone you're trying to get inside of with the music. To try and write music for machinery doesn't appeal to me very much. Some people find character in automobiles. I don't. It's human situations that are attractive to me. That's why A Patch of Blue was a very special project.

kc: Your job is to find a way to write music that supports the drama while the audience gets inside the drama after your work is done. But do you ever try and imagine yourself as part of the audience while you're composing?

jg: Before I begin to write, I try and view the picture the very first time as if I were one of the audience. What am I feeling from this movie as part of an audience? Then, as I ruminate over my responses, I try to think about whether I'd feel those situations even deeper if I added music to it. That's how I try to approach any film. Many times there are certain emotions that got into the picture that may not have been what the director intended, but on the other hand, the music has the power to change that around. There's a marvellous example of that which happened in Logan's Run. The whole last part of the movie was done very romantically and lushly. The producer told me, "You made this into a love story." And I said, "Wasn't that always apparent?" He said, "No." I sometimes wonder how people make these films and not understand what they're doing. Some projects get so overwrought and overproduced that the studio heads are not aware of what it is. I try to think of what's apparent and what's not. In Poltergeist, there's a scene I just scored that's terrifying, but I thought it could have gone two ways musically. I could have played the terror and been done with it. But I didn't think that was quite enough. By inserting the emotional conflicts the characters were feeling brought a whole other element to it.

kc: What was the first truly epic Hollywood picture you worked on?

jg: The Sand Pebbles was the first 70mm and six-track stereo movie I had done. And I loved the story and found it very moving. It was also the first time I worked with director Bob Wise, a wonderful person who is also very sensitive to music, and the story afforded me a larger extended palette to work on.

kc: How difficult is it working on such a large project as The Sand Pebbles?

jg: The difficulties have nothing to do with size. You're concerned more with what are the dramatic and emotional problems of the characters in the story. On the other hand, you write an hour, or an hour and ten minutes of music for a film and that's the way it goes now. I'm longing for the days when there's twenty-eight minutes of music in a picture (laughs). Then there's an epic film like Patton which has only thirty minutes of music in it.

kc: For me, that opening march you wrote for Patton is one of the most fascinating pieces you've composed. You start with these echoing trumpet triplets that seem to invoke war through the ages, but you do it also to play into General Patton's belief in reincarnation. Then you introduce a pipe organ playing the main theme in a liturgical tone as if to reflect his religious beliefs before you give us a quick history of the marching band beginning with the fife and drum and leading up to the modern full scale orchestral march.

jg: That's it exactly. There's three basic elements that I built into the opening theme: the archaic, the religious and the military. That's what made the picture intriguing as a composer. It was to spot these individual character traits of a man and to use them by themselves and also combine them contrapuntally in whatever fashion you wanted. And that's what I did there. Sometimes I used the corral, or at other times a fanfare, or I'd put them altogether.

kc: Speaking of mixing and matching musical styles, in Chinatown you mix jazz and atonal classical music.

jg: The producers were always talking about providing a period sound, but I didn't want to approach it that way. I felt that would only be redundant given what was on the screen. After all, I knew that period having grown up in Los Angeles at that time. Chinatown was a situation again where I was trying to get inside the characters and the opening theme itself became a period piece with more updated harmonies. The jazziness only came about because of the trumpet player interpreting it as a blues which was very nice. But the unorthodox orchestral scoring came to me after seeing the picture. It just called for a tapestry of sound before I had any musical ideas whatsoever. This was strange for me. Usually the musical ideas dictate the orchestration whereas this time I heard the orchestration without any ideas musically. Chinatown is one of my favourite scores and one of my favourite pictures, too.

kc: You finally won your Academy Award for The Omen. Were you surprised that you got recognized for this particular score?

jg: I was surprised about everything on that film! Who knew it was going to take off like it did? I think the score is super. The producer had asked me while they were still shooting the picture, and I'd only read the script, what was I hearing in the orchestra? I told him, "I hear voices." He said, "Wonderful. Love the idea." And then I thought, what did I say? Now I'm stuck with this. It was a departure using a Latin text with that choral arrangement. It turned out to be quite a lot of fun.

kc: Star Trek: The Motion Picture reunited you with Robert Wise. Happily?

jg: Yeah. Tough, though. There was nothing much to write to in the beginning – or to the end. I was working for twenty weeks on this picture because the special effects were so slow in coming in. It just took forever. The last piece I recorded was the Klingon scene which I did on a Thursday night and the movie was supposed to open a week later in Washington. We decided to put the soundtrack album together as we were recording the music for the film so it came out at the same time as the movie. But I had fun writing the music. I actually think it's one of the best things I've done. It was one of those great moments for a composer where there wasn't enough time to build the sound effects so the music had to take it all. We didn't have to worry about being killed by the sound effects. But that's also an intelligent choice because when you're floating around in space, there is no sound. It's a vacuum. You either play it silent, or let the music carry it. Whether you liked what Kubrick did with music in 2001, when the music played, by God, you heard the music.

The interview with author Jerzy Kosinski (The Painted Bird, Being There) took place in 1982 while he was promoting his novel, Pinball. The book was written in response to the murder of John Lennon a couple of years earlier. It's the story of a female fan who hunts down a popular rock star by seducing a former classical pianist to help her in the search. The novel examines the motivations of the pop fan: Is she moved more by the artist, or his art? Our talk also came shortly after the release of Warren Beatty's Reds (1982), which examined the life of the American Communist journalist John Reed (Ten Days That Shook the World) who covered the Russian Revolution. In the film, Kosinski played the Soviet ideologue Zinoviev.

Jerzy Kosinski was a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust by living under a false identity. He wrote about that experience in The Painted Bird (1965). Many of his books took up the theme of anonymity and invisibility which, ironically, came to a head in the late Eighties when he was being accused of plagiarizing some of his work. He ultimately committed suicide in 1991. His final note read: "I am going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call it Eternity." Before Eternity knocked, we discussed the subject of anonymity and visibility.

kc: Is anonymity a theme you love to explore?

jk: Anonymity and visibility, both. Particularly in Being There where the invisibility of the character was uninvited. The world didn't expect Chauncey Gardener and Chauncey Gardener didn't expect the world.

kc: In light of this particular theme, don't you find it rather ironic that a brief appearance in Warren Beatty's Reds has given you – the writer – a certain kind of visibility?

jk: Yes. It's interesting. Twenty minutes of Reds increases one's visibility far more than twenty years of writing fiction. Very recently in New York, I went out with two friends of mine wearing one of my silly disguises and they asked me if I wanted to go to some favourite place of theirs. So I went with this disguise that had a different hairline, mustache and sideburns. For some reason, when we arrived at this place, they ran into a student they knew from Yale, and he was a student when I was a professor there. He wasn't my student, but we were there at the same time. In any case, my friends steered the conversation towards Jerzy Kosinski and whether or not this person had met him. And this guy went into this negative tirade about what his friends – who were my students – thought about this silly man. Meanwhile, there I was sitting right next to him drinking my beer, not contributing to the conversation. He turned towards me only once and then left me alone. Clearly, he didn't think I was interested in the subject matter of Kosinski.

kc: That is a lot stranger than being a fly on the wall. What was your reaction to this?

jk: I found myself absolutely fascinated by the whole experience. I was dramatized from within. Even though some of the things he said about me were very unpleasant. Unfortunately, some of the things he said were true, so I found myself wanting to argue with him about some of his points and accepting the others. All together this was a negative experience. I was crushed by some of his comments. I like to think I'm popular. But obviously, I'm not. Still, it was very rewarding.

|

| Kosinski as the Soviet bureaucrat Zinoviev in Reds |

kc: You make it sound as if there are both benefits and dangers to exploring anonymity.