Lost in Translation (Part One): E.L. Doctorow's Ragtime

Ask anyone who loves to read books and they'll tell you that there is nothing worse than seeing a good book badly mangled on the screen. I'm not talking about the literary fetishists, either – the ones who want to see every little detail of the book translated faithfully. (Those folks are already predisposed to disparage movies as a lesser art. They're prepared to hate the adaptation because films, especially if they come from Hollywood, are already guaranteed to desecrate the source material.) Nevertheless, there are books that have indeed been ruined, if not rendered unrecognizable by filmmakers – those who appear either incapable of understanding the text, or are willfully misreading it.

E.L. Doctorow's 1975 novel Ragtime could well be a victim of both a misunderstanding and a willful misreading. Ragtime is a richly textured parable of American lore in which the author performs masterful tricks with the history we thought we knew. Some historical figures are disguised, others are merely alluded to, while a few others are used by name – popping up in the narrative in the most colourful way. In Ragtime, Doctorow captures the spirit of America in the era between the turn of the twentieth century and World War One. But rather than write a realistic account of the period, he creates a sumptuous pastiche, a flip-book chronicle that is, in many ways, already a movie. "[It was] an extravaganza about the cardboard cutouts in our minds – figures from the movies, newsreels, the popular press, dreams and history, all tossed together," wrote Pauline Kael in The New Yorker. "Doctorow played virtuoso games with this mixture – games that depended on the reader's having roughly the same store of imagery in his head that the author did." In calling the novel an "elegant gagster's book," Kael underlined how Doctorow cleverly portrayed American history as a confidence game that tested our ability to separate fact from fiction. As Voltaire once remarked, "History is a game we play with the dead."

|

| author E.L. Doctorow |

The novel opens in 1906 in New Rochelle, New York, with escape artist Harry Houdini swerving his car into a telephone post outside the home of a white affluent family. As the story advances, seemingly random events pop up. J.P. Morgan and Henry Ford meet to exchange thoughts on the subject of reincarnation. Architect Stanford White is assassinated while his mistress, Evelyn Nesbit, becomes political ammunition for anarchist Emma Goldman. Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, bickering over the role of the unconscious, turn up on the Lower East Side, with Freud desperate to find a public toilet. After visiting Niagara Falls, the fifty-three-year-old father of modern psychoanalysis has "had enough of America," and sails back to Germany. "He believed the trip had ruined both his stomach and his bladder," Doctorow wrote. All through Ragtime, Doctorow mixes historical icons like J.D. Rockefeller and Booker T. Washington with fictional creations like Younger Brother and black ragtime pianist Coalhouse Walker Jr. (based on the hero of Heinrich von Kleist's 1810 literary classic, Michael Kohlhaas), who becomes the victim of a racist practical joke.

The key figure in the novel is an immigrant Jewish merchant referred to as Tateh (Yiddish for "Father"), who lives in a tenement on Hester Street with his young daughter. Tateh cuts out paper portraits of people he meets in the street, an act that develops into flip-page movie books. Eventually, he creates a new identity for himself as the Baron, a film producer. His silhouettes – metaphors for the ongoing assimilation of the immigrant emigré – become Doctorow's key American emblem. The other, of course, is the ragtime music that gives the novel its title. As a musical form, ragtime appeared in the mid-1890s, piano music defined by Irving Berlin as "virtually any Negro dialect song with medium to lively tempo, or a syncopated rhythm." In other words, it was a musical hybrid, a symbol of the American melting pot. Ragtime music may have had an African-American rhythmic style, but it also drew on the European emphasis on written-out compositions.

By the end of the novel, the Baron sheds his disguise to reveal himself as "a Jewish socialist from Latvia" and proposes marriage to the woman from New Rochelle whose telephone pole had been clobbered by Houdini. They head to Hollywood to produce the Our Gang comedies, which featured an ethnically mixed cast of characters. Drawing the ragtime era to a close just as the First World War emerges, Doctorow declares that "history was no more than a tune on a player piano." What he understood was that America remained a culture in flux, a land where the American identity was never static. Literary critic Leslie Fiedler once wrote that being an American "is precisely to imagine a destiny rather than to inherit one." So Doctorow imagined a country that resembled a lively card game running long into the night, where wild stories were traded, jokes shared and anecdotes laid down with the assurance of a flush hand. His pen dipped in the well of the tall tale, Doctorow took what he knew of historical fact and imagined the outcome.

|

| Director Milos Forman with James Cagney |

If Doctorow's shrewdly mischievous sense of fun informed Ragtime, the story couldn't have been more ill-suited to emigré film director Milos Forman. In his Czech films, especially Loves of a Blonde (1967) and The Fireman's Ball (1971), Forman had developed a politically charged neorealistic comic style, but it had huge shortcomings. Whether he wanted audiences to identify with or laugh at the follies of ordinary people, the tone often came across as churlish. It wasn't that Forman hated his characters exactly, but he didn't trust the transformative magic of movie art to make human absurdity engaging. This may be one reason why Forman's films are not only visually drab, but his characters always seem to be pinioned in front of the camera. When Forman came to the United States, his movies developed another problem – they appeared to be largely out of touch with the culture. With the exception of his strong adaptation of Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), in which he wisely eliminated some of the excesses of Kesey's parable, Forman's other American films are hollow and shrill. His adaptation of the musical Hair (1979), despite its energy, missed much of the childlike spontaneity of hippie rebellion captured in the stage version. Like many other Eastern European artists who lived under the repression of Communism, what Forman truly lacked was an appreciation for the vulgar juices that propel American popular culture – exactly what Doctorow celebrates in Ragtime.

Milos Forman wasn't the first choice to direct the film. After Ragtime was published, three things looked certain: Dino De Laurentiis would produce the movie, E.L. Doctorow would write the script, and Robert Altman would direct it. In the end, only De Laurentiis would survive the trio. Altman already had a string of films, McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), The Long Goodbye (1973), Thieves Like Us (1974) and Nashville (1975) demonstrating quite convincingly why he was ideal for the project. He had an amazing aptitude for mixing genres, he worked brilliantly with large casts and he had an unparalleled intuitive grasp of the layered textures of American popular culture. Not surprisingly, he was excited about the possibilities of directing Ragtime. Maybe a little too excited; he started doing his own version of Ragtime while still directing Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976), mixing and matching historical and fictional figures. But somehow Altman wasn't able to bring the Buffalo Bill myth to life and the film came across as cluttered. It bombed both critically and commercially. This turned out to be unfortunate. De Laurentiis, who had money invested in Buffalo Bill, also owned the rights to Ragtime. When Buffalo Bill tanked, he took Ragtime out of Altman's hands and gave it to Milos Forman. Since Doctorow was wedded to the Altman deal, he was pushed out and Forman chose a new script from Michael Weller, the screenwriter who worked with him on Hair.

|

| Robert Altman's Buffalo Bill and the Indians |

It's hard to say just what Forman and Weller thought they were aiming for in their version of Ragtime, since the movie misses the mark in just about every conceivable way. The film doesn't even begin to approximate the themes in Doctorow's novel. Many of the historical figures – Houdini, J.P. Morgan, Booker T. Washington and Stanford White – are either tangential to the story, relegated to a newsreel, or given graceless cameos. Emma Goldman, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and Emiliano Zapata don't even appear in the film. Despite the elegant casting of James Cagney (emerging from a twenty-year retirement to play Police Commissioner Waldo), Pat O'Brien as a lawyer and Donald O'Connor as – what else? – a choreographer, Forman doesn't develop their scenes; his only apparent purpose in casting the characters is simply to have them appear on screen. Ragtime is essentially reduced to one story: Coalhouse Walker Jr's.

Instead of creating a panoramic entertainment, where American history could be understood as much through our consciousness of it as it is from our grasping of facts, Forman interpreted Ragtime, with its emotionally scarred black piano player, as a solemn and literal civil rights story. In doing so, what Forman missed out on conveying was Doctorow's more spirited and wildly playful American jamboree.

-- November 14/12

Lost in Translation (Part Two): Bernard Malamud's The Natural

If Ragtime was a case of the wrong man hired for the wrong job, however, The Natural (1984) was an example of smart and talented people dropping the ball. Bernard Malamud's first novel was a canny parable written with true American gusto in which the author digs into the spirit of one of Ted Williams' famous declarations. Looking back on his storied career with the Boston Red Sox, the baseball great once remarked, "All I want out of life is that when I walk down the street folks will say, 'There goes the greatest hitter who ever lived.'" Malamud asks the question: If you were the greatest ball player who ever lived, blessed with extraordinary athletic gifts, could you just as easily piss it all away?

Malamud's 1952 novel The Natural is a vivaciously entertaining story of a thirty-four-year-old rookie named Roy Hobbs who gets a second shot at becoming a baseball star – and then blows it. Fifteen years earlier, as a can't-miss-prospect, Hobbs is almost killed by Harriett Bird, a disturbed baseball groupie who seduces and shoots him. Years later, and recovered from his injuries, Hobbs gets a new contract and arrives at the dugout of New York Knights' manager Pop Fisher to join the team. Given Hobbs' age, Pop is initially reluctant to bring him on board. His corrupt partner, Judge Goodwill Banner, has also been dumping lousy players on him all year with the purpose of decimating the team; he figures if the team finishes last, Pop will give up and sell him his share of the franchise. Hobbs changes all that by leading the Knights to a league pennant. But he's also an unbridled hedonist. When he gets involved with Pop's niece, Memo, he's distracted from his quest to be the best, just as he was earlier by Harriett, once again betraying his natural gifts. He may be a natural, Malamud reminds us, but he's still human.

As Doctorow did in Ragtime, Malamud adroitly weaves fact and fiction. For instance, as a player, Pop Fisher once committed a blunder ("Fisher's Flop") that cost his team the World Series, a faux pas loosely based on the story of the New York Giants' first baseman Fred Merkle, whose error cost his team the pennant in 1908. Malamud's sports writer, Max Mercy, is obviously based on Ring Lardner, and Walter 'Whammer' Wambold, a lumbering slugger Hobbs strikes out as a brash nineteen-year-old in the book's opening moments, is most certainly Babe Ruth. Judge Goodwill Banner has shades of former Chicago White Sox owner Charles A. Comiskey, who treated his players so badly they went into cahoots with gangsters and threw the 1919 World Series in the famous 'Black Sox' scandal. These rich associations make Malamud's novel a perfect fit for the movies, and as it happened the plot was already based on one: Elmer the Great (1933), an adaptation of a play by Ring Lardner and George M.Cohan and the second in a baseball trilogy starring Joe E. Brown as a loudmouthed rookie who attempts to break in with the Chicago Cubs.

|

| Barry Levinson, Roger Towne and Robert Redford |

The Natural, like Ragtime, was promising dramatic material. What was also promising was that Barry Levinson was brought in to direct it. Levinson had been a career screenwriter who had only recently turned to directing films. His debut behind the camera was Diner (1982), a beautifully written and directed autobiographical comedy about a group of friends in Baltimore at the end of the Fifties. The picture was remarkably perceptive, a truly fresh and honest view of sexual relations between men and women on the cusp of the sexual revolution. Diner launched the careers of a number of talented actors like Ellen Barkin, Mickey Rourke and Kevin Bacon, and featured the lone great performance by Steve Guttenberg. So with Levinson in charge, a script written by Roger Towne and Phil Dusenberry, and shot by the justly acclaimed cinematographer Caleb Deschanel (The Black Stallion, The Right Stuff), the movie seemed ripe with possibilities. But instead of being a hip, funny yarn, The Natural became an overripe and gauzy piece of nostalgic whimsy. The film totally changed the meaning of the book by becoming a hollow piece of hero worship.

Their horrible reworking of the story, in which Roy Hobbs fulfills his destiny rather than flubbing it, had everything to do with the casting of Robert Redford as Hobbs. By the 1980s, Redford, as an actor, had grown lazy being a huge movie star and his performance here was indistinguishable from a politician running for high office. Rather than portray Hobbs as a man who could not resist temptation, he plays him as a hero triumphing over adversity. Hobbs may be mythic in the novel, yet we never forget that he's possessed with human frailty. But Redford's Hobbs is a Golden Boy who is beyond temptation; an innocent country lad whom city folks try to corrupt. Once again a hopeful and spirited work of fiction became a tired formula. Redford's saintly performance has the adverse effect of turning Malamud's pointed prose into processed movie corn. As a result, The Natural becomes canned Americana.

-- November 15/12

2013

Singer of Songs: Malik Bendjelloul's Searching for Sugar Man

|

| Sixto Rodriguez in Searching for Sugar Man |

Though Stone Reader is certainly a one-of-a-kind story, it may well have found its perfect soul-mate in Searching for Sugar Man (which is coming out on DVD this month). This Swedish/British co-production, directed by Malik Bendjelloul, is also about a quest for an artist who has become lost in time. But unlike Mossman, who never caught the larger reading public's imagination, Sixto Rodriguez, an American pop artist unacknowledged in his homeland, became a near legendary figure miles away in South Africa where he turned out to be as big as Elvis. The rousing aspect of the picture comes in seeing just how Rodriguez's music unwittingly becomes part of the spirit of a people fighting for social and political justice against apartheid. What's curious, however, is that Rodriguez's work isn't the most obvious form of political agit-prop to be embraced by a cause. Instead he writes delicately poetic and engagingly impressionistic songs of social realism; tunes which stoke the imagination rather than tear down walls. Searching for Sugar Man follows the efforts of two Cape Town fans, Stephen 'Sugar' Segerman and Craig Bartholomew Strydom, who try to find him in the post-apartheid years.

Rodriguez, a Mexican-American singer-songwriter discovered in a Detroit bar in the late Sixties, doesn't possess the dynamic voice of a rabble-rouser. He sings in a light tenor that resembles a less affected José Feliciano with a literary frame of mind. His first album, Cold Fact, released in 1970, features figurative songs like “Sugar Man” (about drugs) and “Crucify Your Mind,” which for some suggest the strong influence of Dylan. But Cold Fact actually has more in common with the social protest heard a year later in fellow Detroit artist Marvin Gaye's What's Going On. (Like Gaye, Rodriguez also has a song on his record called “Inner City Blues.”) But where Gaye's landmark R&B album would have a seismic impact on both his career and on popular culture, Rodriguez's release took him down the road to obscurity. Although Rodriguez followed up with a strong sophomore effort, Coming From Reality, in 1971, with equally good material (including the song “Cause” which sounds like early Townes Van Zandt on a sunny day), he was quickly dropped from his record label and disappeared into the world of manual labour to raise his family. (His two lovely daughters are interviewed throughout the picture and they articulate with great affection their father's humble demeanour, as well as speaking with pride about how he continued to create a value for art in their lives.)

Searching for Sugar Man reveals how a mythical life can become part of urban legend, too, in the same manner as Elvis. Over the years, many have spotted the supposedly dead Elvis pumping gas, or eating burgers in some highway diner, while Segerman and Strydom thought Rodriguez had committed suicide on stage during a concert in the Seventies. (The ghost of Johnny Ace might have been impressed.) Their glee at finding him alive is only matched when they are able to convince him to journey to South Africa to perform a concert and meet his adoring fans. Instead of a recipe for failure, where this then 50-year-old artist attempts to meet an audience he never had a chance to attract at home, the show (with local musicians who memorized his bootlegged records) is a roaring success. What is maybe most surprising is just how at ease he is with the sudden acclaim. There is a Zen-like acceptance of his fate as if he believed that all things come in their time. That same Zen acquiescence seems to have influenced Bendjelloul as well. He directs Searching for Sugar Man simply, letting the beauty of the story tell itself, while never getting in the way. Bendjelloul doesn't appear awed by what he uncovers either, which benefits the film because it allows us to discover Rodriguez and his music for ourselves. (His albums, plus the movie soundtrack, are now all available on CD.)

When Lou Reed and Frank Zappa once separately traveled to the Czech Republic after the Velvet Revolution of Vaclav Havel, they were both overwhelmed to discover that fans in that country went to jail for owning their records. Listening to the testimonials of individuals who were beaten and tortured for listening to their music provided for them a sobering perspective on their global influence. (These two controversial performers had faced only censorship in their homeland.) Searching for Sugar Man is a whole other version of the American artist perceived from abroad. While Reed and Zappa had clearly defined personalities, Rodriguez's persona was one invented by the South Africans who came to embrace him. The more you watch Searching for Sugar Man, the less it seems like a documentary. It's more of a fairy-tale mystery – an inspirational saga without a whisper of sentimentality.

-- January 1/13

Pulped Fiction: William Friedkin's Killer Joe

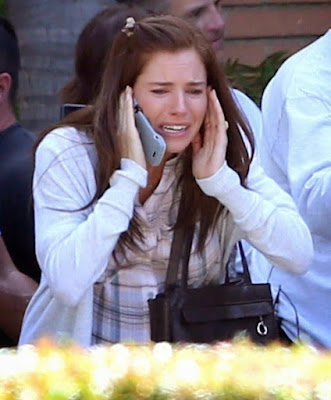

|

| Matthew McConaughey as Killer Joe |

There's no written rule on what makes the best film noir. But you could say that its enduring appeal isn't simply in watching the downward spiral of desperate characters. Its attraction also lies in sharing the horror of that trip down the road to perdition. For all of Fred McMurray's tough-guy assertions in Double Indemnity (1944), for instance, we develop some empathy for him when we see that he's essentially the sap that Barbara Stanwyck takes him for. In The Grifters (1990), when Anjelica Huston chooses the money over the life of her own son, we understand in our bones her primal need to make that choice (while getting the cold shakes from knowing the death rattle chill she will forever carry within her). The darkness in film noir always works best when we can first see the light that's being snuffed out. If we can't perceive something of ourselves in its doomed characters then the genre simply becomes an empty exercise in nastiness.

William Friedkin's Killer Joe (which recently came out on DVD) is a perfect example of that kind of emptiness. This particularly vicious noir, an adaptation of Tracy Letts's celebrated 1991 play, and elegantly shot by Caleb Deschanel (The Right Stuff, The Black Stallion), takes a particular glee in rubbing our nose in nastiness. (There are quite a few pretty good noirs that have a similar nasty and sadistic tinge, like Mike Figgis's 1990 Internal Affairs, but Killer Joe has no interest in psychological nuance and dramatic colour like Figgis's work which cleverly employs the theme of jealousy in Othello.) To compensate for the emotional distance Friedkin creates here, the director provides a hip and ironic comic tone that diffuses the power of the violence in the drama. Friedkin (who made his career with brutally basic entertainments like The French Connection and The Exorcist) adopts a clever pose instead, one that makes us feel superior to the people on the screen. In doing so, he invites us to enjoy the sadism when it gets predictably turned on them. Speaking as bluntly as the action itself: he makes them too dumb to live.

Killer Joe is your archetypal noir. Chris Smith (Emile Hirsch) is a young drug dealer who lives in a trailer park in a small Texas town with his virginal younger sister Dottie (Juno Temple). When he finds himself in a considerable amount of debt to the local loan shark, he figures his only way out is to murder his mother to collect her $50,000 of insurance money. (His mother's boyfriend tells Chris, in a rather inexplicit plot point, that his sister would be the sole beneficiary of the cash.) Figuring Dottie would be generous enough to split the cash, Chris involves his father, Ansel (Thomas Haden Church), his mother's ex-husband, into his criminal conspiracy. Ansel agrees to come on board as long as his current wife, Sharla (Gina Gershon), gets a cut of the cash. To accomplish the deed, Chris hires Joe Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), a police detective who is a contract killer in his spare time. When Chris ultimately can't fully meet Joe's fee, Joe proposes that Chris offer up Dottie as a 'retainer' until the insurance cash comes through. As in most noirs, nothing goes as planned and retribution becomes the story's point.

In Killer Joe, though, Friedkin (who had already adapted Letts's 1996 play Bug) focuses on punishing the characters rather than bringing out anything in the way of motivation for their behaviour. For instance, Chris is in so much debt that in such a small community it's a wonder anyone would let him get that deep into their pockets. Given his penchant for losing, too, it makes even less sense that Ansel would confidently go along with the plan. There's a bit of business of family incest as well that is never fully explored and Dottie's character is no more than a retread of Tennessee Williams' Baby Doll. What Friedkin provides instead of compelling drama is a portrait of trailer park life no more incisive than an episode of The Jerry Springer Show. According to Killer Joe, you'd think these people deserve their fate because they represent what Friedkin and Letts see as the kind of American lowlife who buys tabloids and watch junk on television. They already judge these folks for their bad taste. (The first shot of Gina Gershon, who is made deliberately unattractive here, is her opening a trailer door with her naked crotch facing the camera. Is that what constitutes nuance for Friedkin?)

|

| Emile Hirsch and Matthew McConaughey |

But if the principal characters are left redundantly unappealing, Joe Cooper is the picture's ace in the hole. While everyone else is encouraged to act up a storm, Matthew McConaughey settles in and anchors a riveting performance that is perfumed in quiet menace. Although his character makes about as much sense as anything else in the film (who knows why he's a contract killer, or even how he accomplishes this task without alerting his superiors?), McConaughey plays what amounts to a vibe with about as much gravity as an actor can bring. But maybe it's the character's lack of dimension that provides a certain strategy for the star. Early in his career, when McConaughey tried to be both a serious actor and a movie star, in movies as diverse as Lone Star (1996) and A Time to Kill (1996), he couldn't provide the emotional weight to carry them off. He came across as Paul Newman with the soul of a surfer dude. But in his later career, he's taken to concentrating his characteristic lightness into something that disguises a restless darkness lurking beneath. It's as if he's found a way to use his limited range as a foil to overshadow the unacknowledged depths of a character we would normally find superficial. As Joe Cooper, McConaughey peeks beneath the genial demeanor we've come to recognize in him and he now shows us the explosive energy it was holding back. (It's a shame this performance isn't in a better movie. One of his most dynamic moments comes at the expense of sexually humiliating Gina Gershon in an ugly scene staged so poorly that it upstages a thinking actor's work – it also earned the picture an NC-17 rating in the United States.)

Perhaps what trips up Friedkin most in Killer Joe, besides his basic brutalism, is that he has no feeling for the pulpy material he's adapting. When Raymond Chandler once talked about writing detective novels, he spoke about choosing a particular vernacular that didn't pander to his audience, but instead would be in a language he knew his readers would understand. Friedkin, on the other hand, seems to feel that he's so much better and smarter than the material in Killer Joe that the film's language is deliberately mocking. So he doles out the brutality, but he can't risk identifying with the people on the screen acting it out. By condescending to the material in Killer Joe, Friedkin not only reveals the heart of a snob, he doesn't do full justice to the pulp in the fiction.

-- January 20/13

The Hindsight of Time: Ben Affleck’s Argo

There are a number of good reasons why many of the post-9/11 movies (In the Valley of Elah, World Trade Center, Reign Over Me) have failed to come to terms with the aftermath of that tragic moment and the subsequent wars that followed. Besides depicting those events through conventional melodrama employed only to stir audience empathy, these films actually leave little to the imagination.While trying to make sense of a time that is still being played out, each movie leaves scant room for reflection. This might be why Zero Dark Thirty, a movie about the mission to kill bin Laden, fails to resonate with the power the subject warrants. Despite all the heated debate about the picture’s point of view on torture, for example, director Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker) actually backs away from the dramatic core of that subject.

While I think it’s clear that she isn't endorsing waterboarding as a means of getting information, she also isn’t delving into why it would be a considered means of interrogation for tracking down the mastermind of 9/11. Her picture simply depicts the steps of that quest, the full facts not withstanding, but she leaves out the dramatic ambiguities that would give the story a quickening pulse. The performances in the movie are also so attenuated, so inert, that the actors can't take us into the larger, more disturbing questions which means they never get engaged (despite the media hoopla). Zero Dark Thirty fails, for instance, to even bring to light how national policy has changed significantly from the era of the Cold War (where two superpowers with the ability to incinerate the planet tried to avoid that catastrophe) to the post-9/11 period (where the enemy isn’t concerned with what happens in this world, but rather the possibility of salvation promised in the next one). These uneasy examinations of interrogation, international security and the subject of terrorism (which has a whole different cast when seen in the context of religious fundamentalism instead of the secular kind offered by Communism) are not being explored in these 9/11 movies because the thinking in them hasn't moved past the tropes of the Cold War years. They may be contemporary films about post 9/11 but they end up feeling stuck in the past.

During the Vietnam era, American directors couldn't depict the war in Southeast Asia, so they sought instead to capture the country’s mood indirectly through period pieces (Bonnie and Clyde, The Godfather), horror films (Night of the Living Dead) and earlier wars (M*A*S*H*). Those pictures (and many others, good and bad), didn’t make declarative statements about their time; they were deeply felt impressions of a tumultuous period in political and cultural history. All these years later, many of them still have the power to resonate (whereas Zero Dark Thirty, with its lack of urgency, seems to be already disappearing from public memory). However, when considering Ben Affleck’s equally controversial, yet highly entertaining, Argo, you can see more interesting dramatic ideas at work. Looking back at the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis, Affleck gives his story (despite its various inaccuracies) something of an arc that takes us to the present. And even if Argo is consciously designed as a commercial crowd-pleaser there is still a deeper story under the thrills. Argo also says something about the decade that followed the period that this movie covers. Perhaps proving that not all commercial projects created for a mass audience get corrupted by corporate culture, Argo displays the presence of an artistic sensibility that lurks under its clear desire to entertain.

|

| John Goodman, Alan Arkin and Ben Affleck |

Based on an article by Joshuah Bearman (“How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran”) in the April 24, 2007 issue of Wired, Argo is a nimble dramatization of how CIA operative Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck) led the rescue of six U.S. diplomats from Iran during the revolution that brought the Ayatollah Khomeini and his medieval brand of Islamic fundamentalism to power. More than 50 of the embassy staff were taken as hostages, but six escaped and hid in the home of the Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor, here played by Victor Garber. After exhausting a number of possible plans for extracting the hostages, Mendez creates a cover story inspired by a television viewing of Battle for the Planet of the Apes with his son. He tells his supervisor Jack O’Donnell (Bryan Cranston) to get him in touch with Hollywood makeup specialist John Chambers (John Goodman) who has often prepared disguises for other CIA operatives. Through him, they contact film producer Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin), who sets up a fake studio that publicizes a plan to make a science fantasy film in the style of Star Wars called 'Argo.' The idea is to enter Iran and provide the six escapees with false Canadian passports and identities depicting them as the film crew for this fantasy picture which is scouting Iran for the possibilities of shooting it there. The tension in the story derives from the contrast of the revolutionary government’s attempts to find the missing embassy workers (by having children putting together the shredded paper containing their identities) and Mendez inspiring trust in the group that his plan will work.

Some of what truly happened during the hostage crisis has been jettisoned here, especially the role of Ken Taylor (who did way more than just open and close doors). And this particular thorny point has taken up most of the debate about the film (as well as ideologically flavoured accusations of racism towards the film's depiction of the Iranians). But rather than damn Argo because of the typical American ignorance about Canada, or its inability to provide a more nuanced understanding of the Iranian people, it might be more worthwhile drawing as much attention to just how well crafted the picture is. As a director, Ben Affleck has already shown a keen and intelligent eye for popular storytelling. His first picture, Gone Baby Gone (2007), was not only a crackerjack procedural but it was also a terrific chamber ensemble for a number of the performers. (He even miraculously elicited the first wide-awake performance from his brother Casey Affleck.) His follow-up picture, The Town (2010), had an inferior, less-believable script, but the direction was swift and the actors – especially Jeremy Renner who brought a bit of James Cagney’s balletic intensity to his role – made the movie worth seeing.

Argo might be his strongest, most confident picture yet because it has more going on than just a desire to whip up enthusiasm (despite the invented climax of a last minute airport escape which is too derivative of other action pictures). Affleck’s Mendez isn't a typical hero, despite his success rate as a CIA operative, because he performs his duties with a self-effacing precision. Despite his height and handsomeness, Affleck always looks as if he’s in the process of finding his own feet (much like the equally bearded Warren Beatty did as the frontier town dreamer in Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller) which makes him a more appealing saviour because he doesn’t act out of self-righteousness. (When he returns from his mission, he’s told that President Carter called him a great American. “A great American what?” he asks. “He didn’t say.”) But this underplaying of heroism is germane to the general theme of the film.

|

| Affleck directs Argo |

Argo takes place towards the end of the Seventies, a decade when American heroism was tainted by the assassinations of the Sixties, plus the dirty tricks of the Nixon years and Watergate; and on the cusp of the Eighties, when Ronald Reagan became President, and his regime helped usher in a decade of fantasy superheroes that brought back jingoism as a popular adventure model. In Argo, Affleck shows us that the fictional fantasy film, which Mendez uses to spirit the hostages away, had only just made a comeback through the popularity of Star Wars in 1977. During the conclusion of Argo, however, when the camera pans over a young boy’s bedroom filled with Star Wars toys and other comic characters, we get a clue about the decade ahead. ‘Argo’ would ironically become the predominant model in American commercial action cinema. We would even have a former B-movie actor as President of the United States.

Argo begins with a comic strip history lesson showing how the American overthrow of a democratic regime in Iran led to the tyranny of the Shah which ultimately sewed the seeds for the religious zealotry to follow. The point here however is not to reduce history to comic-book simplicity, but to show us how these shorthand visual depictions create powerful visceral responses that movies tend to enhance. Affleck is trying (in an age when formula dominates American movies) to execute a meaningful use of formula and showing us how you can use it to breathe life into a complex story (while sometimes having to leave out the complexity). Although fundamentally Zero Dark Thirty is a more ‘serious’ work than Argo, it’s Affleck’s film that lingers as the more affecting movie. He dares with the hindsight of time to inventively toy with popular formula styles; those styles that today get reduced to largely impersonal forms of entertainment. Zero Dark Thirty, on the other hand, deliberately avoids the temptation of boiling the blood with commercial cunning. Bigelow resists moving with emotional complexity into the dirty areas of the so-called War on Terror. But Argo finds its life by confidently using contemporary popular forms in order to provide a reflecting mirror of the past. The film not only doesn't get mired there: it stares straight ahead into the present. And like the best of Seventies commercial cinema, Argo shows no signs of ever dying on the screen.

-- February 17/13

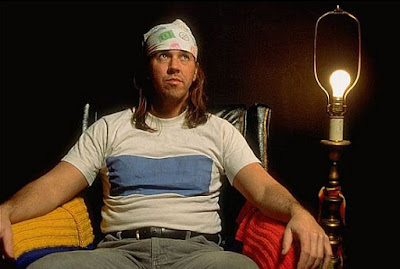

American Composer: Frank Zappa's Understanding America

“It's all one album,” Frank Zappa once told journalist Jerry Hopkins in characterizing his work during an interview for Rolling Stone magazine in 1968. With only three releases to his credit, and long before he'd come to accumulate close to 100 records of satirical rock, orchestral, ballet, electronic and jazz scores, Zappa already fully grasped the “conceptual continuity” of his project/object. “I could take a razor blade and cut them apart and put it together again in a different order,” he said. “It still would make one piece of music you could listen to.” In 1993, a couple of years before he would die from prostate cancer, Zappa followed through on that suggestion. He took a razor blade to his back catalogue with the purpose of creating a caustic, but passionate musical portrait of the nation that produced him. Understanding America is a two-CD musical anthology unceremoniously put out last fall by Zappa Records through the distribution of Universal (who recently re-released, with huge sonic improvements, his large body of work). But given the little fanfare provided its arrival, you might as well call it The Mystery Disc. The CD comes with a stark 1975 black-and-white photo of the composer on the front cover, a didactic title, no track listing on the back cover, no accounting of the various musicians who play on it, no background notes on the songs (including which year they were recorded and what albums they first appeared on), and scant explanation concerning the context of the new album except for cryptic pronouncements that it's a record about “love, peace, justice and the American way.” (Its very design prompted a friend of mine who saw it to ask: “Is this a bootleg?”)

If the proposed audience for Understanding America is the Zappa fan, it might make sense to avoid redundancies by leaving out information that's already been absorbed into the DNA of the initiated. But what will the uninitiated make of this release? Some fans have already panned the album on websites and chat rooms complaining that it uses the old reverb-drenched digital mixes instead of the new cleaner and dryer ones (but what other mixes would he use since Zappa sequenced this release while he was still alive?). They're also arguing about the inclusions of some songs and the omissions of others (as if this were yet another 'greatest hits' package). How about the new listeners to Zappa's music? Since it's unlikely to get reviewed by contemporary pop critics, Understanding America not only doesn't stand a chance of being understood, it likely won't be realized either. And that would be a huge loss. Drawing from a vast and varied selection of Zappa's compositions, Understanding America is a musical jig-saw puzzle piecing together a political heritage embroidered with assassinations, deep racial divisions, religious zealotry, cultural elitism, and witch hunts. (The album traces chronologically – with a couple of detours – the dramatic changes in the political and social landscape from the era of Lyndon Johnson to the end of the first Bush presidency.) It also provides a unified field theory of Zappa's disparate selection of songs. Understanding America gives listeners a perceptively potent framework; one in which to examine the conflicting characteristics of American life, as well as providing a completely new contextual ground in which to experience Frank Zappa's music. One of the great ironies of Understanding America, however, is that the work included on it ended up embraced more by dissidents behind the original Iron Curtain (who even did prison time for embracing it) than by Americans deprived of his music by radio stations who censored it. Understanding America sets out to test the strengths of American democracy, too, by holding the country to the promises held in its founding documents by primarily shedding light on its failings. And because of Zappa's openness to such diverse musical genres, he draws from a huge storehouse of self-expression to do so.

By actually combining serious contemporary music with rock, jazz, and social and political satire, Frank Zappa became one of North America's most ambitious artists. No musical ghetto could contain or define him, and no sacred cow or social group was beyond his reach. Zappa created a unique and sophisticated form of musical comedy by integrating into the canon of 20th-Century music the scabrous wit of comedian Lenny Bruce and added to it the irreverent clowning of Spike Jones. His body of work, both solo and with his band, The Mothers of Invention, presented musical history through the kaleidoscopic lens of social satire, and then he turned it into farce. Zappa poked fun at middle-class conformity (Freak Out!), the Sixties counter-culture (We're Only in it for the Money), disco (Sheik Yerbouti), the rock industry (Tinsel Town Rebellion), and the Reagan era (You Are What You Is). He was just as content writing inspired orchestral compositions – performed by the London Symphony and the Ensemble Modern – as he was writing seemingly dumb little ditties like “Dinah-Moe Humm” or “Valley Girl.” He could just as readily quote contemporary classical giants like Igor Stravinsky, Charles Ives, Edgard Varèse and Anton Webern; or blues greats like Johnny 'Guitar' Watson and 'Guitar' Slim; not to mention, doo-wop groups like The Channels and Jackie & The Starlites. Yet it was these paradoxical elements that the North American mass audience rarely had the chance to engage. The name Frank Zappa instead conjured up the image of a deranged, cynical, and obscene satirist rather than a composer with an impious, yet utopian, ambition to close the divide between high and low culture. People preferred, usually out of ignorance (and often contempt), to portray Zappa as a fetishist with a predilection for adolescent humour (“Don't Eat the Yellow Snow”), and one who possessed a leering smugness (“Broken Hearts are for Assholes”), rather than deal with the specific points of what these individual songs were actually about.

“One of the things that always impressed me about Zappa, besides just the delight with his rhythmic invention, was that he didn't allow anything to be beyond him – high culture, low culture,” said Matt Groening, the creator of The Simpsons. Whether it was in his most scatological songs like "Bobby Brown Goes Down," his political attacks on Christian fundamentalism ("Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk"), or even his testimony before Congress fighting the censorship apparatus known as the Parents' Music Resource Center (PMRC) in the Eighties, Zappa clearly identified the inherent contradictions in American democracy. (The censorship arm of the PMRC wasn't launched by Moral Majority Republicans, who would support it, but by liberal Democrats.) The songs on Understanding America provide an intricate map of those incongruities. But where popular political artists like Woody Guthrie, Billy Bragg, U2, or Rage Against the Machine, tend to make their art explicitly partisan, Zappa's political music transcended the rallying nature of the topical song. He already understood how popular music, borne out of commercial and marketing demands, could always be co-opted by corporate interests who could sell listeners anything deemed fashionable. "Unlike Sting and U2, who ask us to admire their actions on our behalf, Zappa sets up a series of questions about meaning and its social control that encourage our speculation," wrote Ben Watson in his book, Frank Zappa's Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play. Which is why Zappa doesn't identify with the "correct" view in many of his songs; instead, he provides a setting that causes listeners to raise queries about what they are consuming. His music, according to Watson, is "an anathema to liberalism, which thinks that only commitment to certain pre-selected 'ideas' separates the the saved from the damned."

Zappa often picked subjects and people that unnerved listeners who wanted to strongly identify with the artist. “Frank persisted in discussing all those subjects that made people squirm – politics, sex, religion, whatever,” remarked Jill Christiansen, who was the catalogue development for Rykodisc (where Zappa's huge collection was made available on CD in the Eighties and Nineties). “He demanded that you think.” Understanding America makes similar demands on us to think because it isn't just a collection of favourite tunes that take you on a nostalgic tour down memory lane. The album provokes your involvement with its theme because even if you try to “squirm” away from the words, the music leaves you no room to escape. “Something happens...when satiric or erotic texts are sung to powerful music,” wrote poet Ed Sanders, the founder of The Fugs, on Zappa's satirical strategy. “[It] raises their ability both to thrill and excite as well as to prick censorious ears.” It's in those goals that Understanding America succeeds most.

Understanding America opens with “Hungry Freaks, Daddy,” the very first song on Zappa's debut album, Freak Out! (1966). It's a prophetic anthem that sets the tone for both the record and the composer's utopian goals. “Hungry Freaks, Daddy” begins with the inverse of the guitar chords that began The Rolling Stones' great hit “(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction” and then launches into a full-frontal assault on America's stagnant culture (“Philosophy that turns away/From those who aren't afraid to say what's on their minds/The left-behinds of the Great Society”). The Great Society (a term invented by President Lyndon Johnson in 1964 to describe his ideal America) is already deemed false by 1966, so Zappa sees no reason to feel forsaken. But there is a significant difference in the perspective of both songs. “(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction,” released a year earlier in 1965, speaks basically to a state of alienation in the listener. Mick Jagger is expressing frustration at being betrayed by the promises of consumer culture. Zappa is talking directly to the disenfranchised listener, not an alienated one. Jagger may feel cheated because conforming to corporate ideals doesn't make him terribly happy, but the singer in “Hungry Freaks, Daddy” isn't betrayed by the false blandishments offered by the culture. He's already rejected them.

If the false promises of The Great Society are expressed in the opening track, we are introduced to the President himself in the next tune, "Plastic People," originally the first song on Absolutely Free (1967). As a drum roll kicks in, Zappa introduces Lyndon Johnson, just as singer Ray Collins, in the voice of LBJ, addresses the crowd: "Mah fella Americans..." We then hear the intrusive opening notes of Richard Berry's "Louie Louie." Zappa had incorporated "Louie Louie" (a staple for every bar band) as a stock idiom in just about every album he recorded, but it wasn't out of malice to Berry. On the contrary, it was included as a snide indictment of how this lovely Fifties R&B song (with its musical roots in Chuck Berry's lilting Latin melody of "Havana Moon") got turned into a ridiculous frat-house hit in 1963 by an Oregon group called The Kingsmen. (By mangling the words of Berry's song, The Kingsmen famously raised the possibilities of perverse sexual fantasies in the lyrics which drew the attention of the FBI and the FCC who conducted an obscenity investigation.) In doing his own variation of the Kingsmen version of the "Louie Louie," Zappa shows us that even the President of the United States isn't safe from this pervasive song – and neither is the rest of the nation. But "Plastic People" mostly addresses the conformity that Zappa saw creeping into the very counter-culture that he celebrated in "Hungry Freaks, Daddy." He also sees conformity infecting love affairs where truly romantic encounters start to fall victim to trendsetting. (Understanding America continually shifts from song to song, and even within each track, between the political and the personal, revealing that the dynamics of sexual and social politics are often one in the same.) Throughout the tune, Zappa doesn't mince words about how dangerous succumbing to authoritarian ideas can be. In retrospect, "Plastic People" even has a chilling prescience. Just consider these lyrics written only a few years before American Nazis fought to win their Constitutional right to march through the streets of Skokie, Illinois:

Take a day and walk around

Watch the Nazis run your town

Then go home and check yourself

You think we're singing about someone else.

"Plastic People" would take on a larger significance when countries in the Eastern bloc, living under authoritarian Communism, adopted it as their anthem. When Zappa was touring heavily in Europe after the song was recorded, a few fans from Czechoslovakia came across the Austrian border to hear his concerts in Vienna. They told Zappa after the show that the song was responsible for inspiring a whole movement of dissidents growing within their country. One of those rebels was Milan Hlavsa, a Czech rock star, who was the co-founder of an underground band called The Plastic People of the Universe. They supported various other democratic radicals in their music, including playwright Vaclav Havel, during the Seventies and Eighties.

In the next song, "Mom & Dad" (from We're Only in it for the Money), Zappa shifts his attention from the rebellion of adolescents to the complacency of the parents. In this case, it's about a middle-class couple sitting at home drinking who come to learn that their daughter has been shot dead by the police while protesting in the park. Zappa reveals a naked ambivalence towards simply taking sides in this mournful ballad. Yet he still manages to level with every stratum of the culture as he documents the cultural wars of the Sixties. The drinking parents, hiding behind their appearances, end up intrinsically linked to their drug-addled kids ("Ever tell your kids you're glad that they can think/Every say you love them/Ever let 'em watch you drink"). As if to anticipate the obvious question faced when the guns of the authorities get turned on their own citizens, he follows "Mom & Dad" with "It Can't Happen Here" (from Freak Out!). "It Can't Happen Here" is an absurdist a cappella number reminiscent of a barbershop quartet. But there is nothing harmonious in the sound, or in the content of the song. "It Can't Happen Here," not coincidentally, is also the title of the 1935 anti-fascist novel by Sinclair Lewis. In the track, though, the tinge of romantic paranoia ends up inseparable from the absurdity of its social observations. "Who are the Brain Police?" (also from Freak Out!) then introduces with full portentousness why it can happen here: the acceptance of an authoritarian mindset ("What would you do if we let you go home?/And the plastic's all melted and so is the chrome"). As the bass throbs and creaking jail doors seem to surround singer Ray Collins, the idea of plastic also includes the record vinyl, addressing the fetishizing of the product itself in the age of LPs ("What will you do when the label comes off?"). Zappa satirizes the manner in which listeners identify with the music on the album in their quest to form an identity.

"Who Needs the Peace Corps?" (from We're Only in it for the Money) is one of the funniest, yet stinging analysis of the hippie movement and the drug culture that immobilized them ("I'll love everyone/I'll love the police as they kick the shit out of me on the street"). Since the hippie culture was born in San Francisco, the melody also carries the hopeful spirit of Tony Bennett's "I Left My Heart in San Francisco." However, Zappa dispenses with any romantic attachments and more boldly links the passivity of hippie altruism to its ultimate collusion with the authoritarian powers of government. "The single most important [lesson of the Sixties] is that LSD was a scam promoted by the CIA and the people in Haight-Ashbury, who were idols of people across the world as examples of revolution and outrage and progress, when they were mere dupes of the CIA," Zappa told biographer Neil Slaven reminding him of the government mind-altering experiments dosing people with LSD in sleep rooms beginning in the early Fifties. The government itself becomes the subject of the mini-opera "Brown Shoes Don't Make It" (from Absolutely Free) which is also about what Zappa called "people who run the governments, the people who make the laws that keep you from living the kind of life you know you should lead." "Brown Shoes Don't Make It" is a seven-and-a-half minute opus paced at the speed of a Loony Tunes cartoon, and is filled with enough musical quotes and references to inspire a dozen oratorios (the quotes range wildly from The Beach Boys' "Little Deuce Coupe" to Charles Ives). While "Brown Shoes Don't Make It" is a scathing indictment of how authoritarian attitudes are formed, it is also a jab at the sexual revolution of the late Sixties.

|

| Kent State on May 4, 1970 (photo by John Paul Filo) |

Zappa continues his assault on the government in "Concentration Moon" (from We're Only in it for the Money) which attacks the police for its blatant brutality against the hippies ("American Way/How did it start/Thousands of creeps/Killed in the park"). Where "Concentration Moon" significantly anticipated, three years before it happened, the tragic shooting and killing of four students by National Guardsmen at Kent State University on May 4, 1970, the next song, "Trouble Every Day" (from Freak Out!), was a response to the August 1965 race riot in the inner city of Watts – a revolt of such magnitude that it gained worldwide attention. The casual arrest of a black motorist in Los Angeles was the spark that set off this powder keg of frustration. The Watts uprising, brought on by neglect, black unemployment, discrimination, poverty, plus brutality by the L.A. police, raged on for six days. During that week, 10,000 angry people turned Watts into an inferno. As viewers watched on television, rioters burned cars and buildings and looted stores while the riot police were pelted with stones, attacked with knives, and shot at. The National Guard was finally called in, and by the time order was restored, thirty-four people were dead, hundreds were injured, and over 4,000 arrested. Although "Trouble Every Day" shares much of the outrage and purpose of the protests songs of the time, it is also a blistering blues track that spares neither side:

Well, I seen the fires burnin'

And the local people turnin'

On the merchants and the shops

Who used to sell their brooms and mops

And every other household item

Watched a mob just turn and bite 'em

And they say it served 'em right

Because a few of them are white,

And it's the same across the nation

Black and white discrimination

Yellin' "You can't understand me!"

"Trouble Every Day" is filled with many unresolved contradictions – the kind that deprive the listener of the satisfaction of pumping a fist in the air out of solidarity. Heard today, it's just as relevant to understanding the Rodney King riots of the Nineties as it was to capturing Watts in 1965. (It's amazing that no rap artist has ever covered this tune because the lyrics, which are set in the blues, have the propulsive vocal rhythms of a great rap song.) The following number, "You're Probably Wondering Why I'm Here" (from Freak Out!) blows raspberries (in the form of kazoos) in the direction of the uncritical pop audiences at concerts. But what it actually does more successfully is set up the next song, "We're Turning Again" (from Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention), a riposte aimed at the counter-culture of the Sixties. It's here that Understanding America takes its first chronological detour from the music of that turbulent decade by introducing a song recorded in the Eighties. "We're Turning Again," as music critic Chris Federico correctly implied in his work Zappology, is a play on Pete Seeger/The Byrds' "Turn, Turn, Turn," a staple of Sixties idealism. The significance of "We're Turning Again," besides satirizing the failure of the Sixties idealism, is to also remind us that it was Ronald Reagan who was committed to wiping out Sixties reform (even back during that period when he was governor of California). Zappa unleashes an unsparing attack, however, on the pseudo-innocence of the hippie counter-culture, with its naive belief in the goodness of putting flowers in the National Guardsmen's guns:

They're walkin' 'round

With stupid flowers in their hair

They tried to stuff 'em up the guns

Of all the cops and other servants of the law

Who tried to push 'em around

And later mowed 'em down.

This portion of "We're Turning Again" refers specifically to Allison Krause, one of the victims of the Kent State shootings, who the day before her death, put a flower in the barrel of a Guardsman's rifle, saying, "Flowers are better than bullets." The earlier inclusion on Understanding America of "Mom & Dad" (which clearly anticipated Kent State) is echoed in "We're Turning Again" which more explicitly spells out how Kent State contributed to the death of the Sixties counter-culture. Zappa may be at his most sarcastic here, especially towards the decade's tragic icons – Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Keith Moon and Mama Cass Elliot – but he's also aware that, compared to the music heard on radio stations in the Eighties, something of true value had also been lost:

Everybody come back

No one can do it like you used to

If you listen to the radio

And what they play today

You can tell right away

All those assholes really need you.

Zappa saw that, by the Eighties, radio formatting had changed the medium dramatically from a musical outlet into an advertising vehicle.

After "We're Turning Again," which puts the Sixties soundly to bed, the next couple of songs ("Road Ladies" and "What Kind of Girl Do You Think We Are?") usher in the post-Sixties hangover when Zappa turned to examine areas of self-gratification in the Seventies. When he first broke up the original Mothers of Invention, Zappa put together a new, vaudevillian band (featuring Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, the former lead singers in The Turtles) whose satirical strategies centred more on the sexual exploits of rock stars and groupies. As well as recognizing the dramatic changes in the rock & roll culture, with its evolving folklore, he was also taking a page out of Lenny Bruce. Aside from his social criticism, Bruce had also radicalised stage comedy by bringing into his onstage routines the sleazy backstage world of stand-up (highlighted in his amazing "Palladium" number). This strategy gave his work a discomfiting vitality because it confronted audiences with routines that raised questions in them about what is funny and what isn't. Zappa would also do likewise as he chronicled the moribund state of rock culture in the Seventies, including the sexual desperation and megalomaniacal qualities of both stars and promoters. Critic Ben Watson accurately captured this new Zappa ensemble as "designed to expose backstage events at precisely the time when rock was turning into a patronizing spectacle of cosmic proportions." If the Sixties gave us performers who had (despite the drugs) imagined a better country in their music, the new rock in the Seventies gave us "sweaty, horny pop stars whose main interest was in getting laid." The criticism in the rock press towards songs like "Dinah Moe-Humm" (also included on Understanding America), where the goal of the singer is to bet a woman he meets on the road that he can make her cum, came from an exalted view of what rock should be. This is why they dismissed the song as juvenile. But what Zappa was doing was uncovering the reality of rock's low road as a way of exposing some of the hypocrisies in taking the high road.

|

| Frank Zappa performing "I'm the Slime" on Saturday Night Live. |

The second disc of Understanding America opens with "I'm the Slime" (from Over-nite Sensation). The song's subject – television – was seen by many as too easy a target to criticize. But Zappa provides a compelling ambiguity here by identifying with the very object he's attacking. He portrays himself as the slime (even on the front cover of Over-nite Sensation, his scowling face is seen dripping from a TV tube). Singing in a menacing and reverberating whisper, Zappa plays havoc with the listener by assuming a devil-doll role not unlike Joel Gray's MC in Cabaret.

I'm vile and pernicious

But you can't look away

I make you think I'm delicious

With the stuff that I say.

Zappa follows that 1973 song with "Be in My Video" (from 1984's Them or Us album) where the pernicious slime has now distorted our intimate relationship with music in this hilarious swipe at MTV culture and rock videos. Cleverly, Zappa performs the song as a Fifties doo-wop number which reminds the listener of rock's hopeful beginnings in that decade before those ideals became corrupted. He fires barbs at the videos of Peter Gabriel ("I will rent a cage for you/With mi-j-i-nits dressed in white") and David Bowie ("Let'd dance the blues/Under the megawatt moonlight"), even though both artists actually worked imaginatively within the form. But his chief purpose behind "Be in My Video" was to expose the worst excesses of rock video narratives:

You can show your legs

While you're getting in the car

Then I will look repulsive

While I mangle my guitar.

On Understanding America's next track, "I Don't Even Care" (from Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention), Zappa reaches back again to the Fifties to resurrect one of his R&B heroes, Johnny 'Guitar' Watson, to sing this propulsive number about a growing political and economic impoverishment.

Listen! Standin' in the bread line

Everybody learnin' lyin'

Ain't nobody doin' fine

Let me tell you why

I don't even care.

The song carries such an angry bite that it's obvious the singer indeed does care, which makes the track more faithful to the punk aesthetic of refusal than most punk songs celebrated for doing so. "Can't Afford No Shoes" (from One Size Fits All) further examines the Seventies economic recession while showing how the Seventies generation at root was simply looking to survive ("Can't afford no shoes/Maybe there's a bundle of rags that I could use/Hey anybody, can you spare a dime/If you're really hurtin', a nickel would be fine"). Out of the spiritual and economic depression, though, Zappa takes us into the Eighties with "Heavenly Bank Account" and "Dumb All Over" (from You Are What You Is). In these tracks, Zappa unveils the rise of the born again Christians. There had always been a strain of messianic preoccupation in the Sixties counter-culture (expressed in films like Easy Rider). During that time, Jesus became a symbolic hippie doomed to crucifixion by the power structure, as he was in the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar. Songs like "Put Your Hand in the Hand" by Ocean, "Day by Day" from Godspell, "Signs" by the Five Man Electrical Band, and "Spirit in the Sky" by Norman Greenbaum further drew the link that led many disillusioned social activists instead to a life of religious deification. But Zappa recognizes also that this hippie romanticism had shifted in the Eighties: the hippie Christ had now been swallowed whole by the yuppie Christ. Those born again were now finding salvation in the mighty dollar. To exploit that desire, the Moral Majority, which was founded in 1979 (and whose name was drawn from Richard Nixon's silently conservative constituents), dedicated themselves to aligning the Church with the State.With the help of Ronald Reagan in 1980, they quickly infiltrated the Republican Party and began dictating policies that bore the strong influence of fundamentalist Christianity:

Cause he helps put The Fear of God

In the Common Man

Snatchin' up money

Everywhere he can

Oh yeah

Oh yeah

He's got twenty million dollars

In his Heavenly Bank Account.

"Dumb All Over,"a great rap number, goes further into showing how religion has done little to foster world harmony, but instead has created a litany of bloodshed:

You can't run a country

By a book of religion

Not by a heap

Or a lump or a smidgeon

Of foolish rules

Of ancient date

Designed to make

You all feel great

While you fold, spindle

And mutilate

Those unbelievers

From a neighbouring state.

If Marx once described religion as the opiate of the people, Zappa says in "Cocaine Decisions" (from The Man From Utopia) that another white powder would become the drug of choice in the Eighties ("Cocaine decisions/You are a person with a snow job/You got a fancy gotta-go job/Where the cocaine decision that you make today/Will mean that millions somewhere else/Will do it your way").Cultural critic Camille Paglia, in Sex, Art and American Culture, also examined the role of cocaine in the new yuppie revolution. "In the Sixties, LSD gave vision, while marijuana gave community," she writes. "But coke, pricey and jealously hoarded, is the power drug, giving a rush of omnipotent self-assurance. Work done under its influence is manic, febrile, choppy, disconnected." In "Cocaine Decisions," Zappa identifies the omnipotent culprit behind that incoherence expressed by those who would come to shape the nature of political and cultural power in the Eighties (and would eventually contribute to plummeting us into the global fiscal crisis in the 21st Century).

"Promiscuous" (from Broadway the Hard Way) is Frank Zappa's first explicit rap song (but unfortunately it isn't as potent as "Trouble Every Day" or "Dumb All Over"). The track tackles the AIDs epidemic as explained by Ronald Reagan's Surgeon-General Everett Koop. In "Promiscuous," Zappa questions Koop's prognosis of the deadly disease. "He speculated about a native who wanted to eat a green monkey, who skinned it, cut his finger, and some of the green monkey's blood got into his blood. The next thing you know, you have this blood-to-blood transmission of the disease," he told Playboy. "I mean, this is awfully fucking thin. It's right up there with Grimm's Fairy Tales." What Zappa fails to acknowledge, however, is that even though Koop was an evangelical Christian conservative, he went against the grain of right-wing supporters by endorsing the use of condoms and sex education to slow the spread of AIDs. He even disturbed Reagan constituents by providing information on AIDs to over 100 million Americans in 1988. Koop also encouraged sex education for children beginning in the third grade.

Zappa's explanation for the AIDs epidemic (which he explores in the next track from his 1984 musical Thing-Fish) ties the epidemic to government experiments in genetic mutation. Fully aware of the LSD experiments conducted by the U.S. government on civilians in the Fifties and Sixties, Zappa felt that the government hadn't abandoned their covert experiments. Furthermore, they may have hatched a mutation of bacteria that inadvertently caused a strain that affected individuals by attacking their immune system. Since the epidemic arrived just when fundamentalist Christianity had found their legitimacy in the Republican Party, AIDs could then be perceived and sold by the Moral Majority as being part of God's plan to punish the wicked. (On television, during that decade, religious leaders like Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell continuously claimed that AIDs was divine retribution from God on its very victims: homosexuals, prostitutes and intravenous drug users.)

After the "Thing-Fish Intro," Zappa goes back in time on Understanding America to his 1979 rock opera Joe's Garage and introduces us to the authoritarian Central Scrutinizer who passes government laws. Joe's Garage is about how the government might wish to do away with music because it is a cause of unwanted mass behaviour. "Environmental laws were not passed to protect our air and water...they were passed to get votes," Zappa writes in the album's liner notes. "Seasonal anti-smut campaigns are not conducted to rid our communities of moral rot...they are conducted to give an aura of saintliness to the office-seekers who demand them." He goes on to say that if listeners find the plot of Joe's Garage to be a bit too preposterous, "just be glad you don't live in one of those cheerful little countries where, at this very moment, music is either severely restricted...or, as it is in Iran, totally illegal." But, by 1985, Zappa found that the United States had become one of those "cheerful" countries where music could indeed be "severely restricted" by an organization called the PMRC.

The Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) was a committee that had the stated goal of increasing parental control over the access of children to music deemed to be violent, or sexual, by labeling albums with Parental Advisory stickers. The group was founded by four women: Tipper Gore (the wife of senator and later Vice-President Al Gore); Pam Howar (wife of Washington realtor Raymond Howar); Susan Baker (wife of Treasury Secretary James Baker); and Sally Nevius (wife of former Washington City Council Chairman John Nevius). The censorial activities of this group were originally inspired by a precociously gifted pop artist from Minneapolis named Prince, who caused a stir with a song from his Purple Rain soundtrack album called "Darling Nikki" (which had a reference to a young girl masturbating with a magazine). Tipper Gore, who bought the album for her eight-year-old daughter, was horrified when the lyric was brought to her attention. So she decided that something must be done through government legislation to protect children from what she found to be unacceptable music. "What we are talking about is a sick strain of rock music glorifying everything from forced sex to bondage to rape," she told Rolling Stone in 1985. The PMRC soon after put together a list of offending songs which included (along with "Darling Nikki"), Sheena Easton's "Sugar Walls," Judas Priest's "Eat Me Alive," AC/DC's "Let Me Put My Love Into You," and W.A.S.P.'s "Animal (Fuck Like a Beast)." The list also reached absurd levels of musical ignorance when tunes like Bruce Springsteen's "I'm on Fire" and Captain and Tennille's "Do That to Me One More Time" also made the cut.

The PMRC within a short time lobbied Congress for strict legislation on record labeling. But instead of having Prince, Bruce Springsteen, or Sheena Easton going on the warpath to Washington to defend their work, it was Frank Zappa, Dee Snider (of Twisted Sister) and folkie John Denver who took charge. (Zappa's songs didn't even appear on their list.) Out of the testimony he did before Congress in September 1985 came a piece called "Porn Wars" (from Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention). This extended piece of sophisticated sampling draws on taped excerpts from the hearings that are speeded up, looped, and layered over-top of one another. The electronic percussive sounds of a synclavier provide a musical bed for the vocal calamity. Zappa's tape experiments, which he first explored with a Dadaist splendour in the Sixties, came to anticipate the politically volatile work heard later in dub poetry, hip-hop and rap.

|

| Frank Zappa testifying in Congress against the PMRC. |

Using the voices of the various senators at the hearing, in a manner that makes their grandiose statements sound robotic and dehumanizing, Zappa brings out the chilling implications of their intent. But he also deftly parodies the monotony of the endless fascination with the questionable lyrics, repeating loops (for instance) of Senator Paula Hawkins' talking about "fire and chains and other objectionable tools of gratifications." "Porn Wars" deserves a place alongside the work of other contemporary composers such as Steve Reich, who early in his career had worked ingeniously with tape-looped voices and music in "It's Gonna Rain" and "Come Out to Show Them" (where he created abstract music out of the timbre of the spoken word). On Understanding America, Zappa extends the original piece (titled here as "Porn Wars Deluxe") by inserting even more sections from the hearings. He also strategically edits into the work various songs from his catalogue (including snippets from tracks we have already heard earlier on Understanding America like "It Can't Happen Here" and "Brown Shoes Don't Make It"). The effect creates a fascinating full circle that further gives new contextual meaning to the very work we had just been re-experiencing in its new setting. Fans will no doubt also notice that some tracks on Understanding America have been edited down, or cut before they conclude, so that each song segues perfectly into the next.

The album could have successfully concluded here, but Zappa decides to go out on "Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk" (from Broadway the Hard Way). In this song, he uses some of the same strategies once employed by Spike Jones (where Jones would use references to familiar songs to spring jokes). Zappa embroiders into this track iconic pieces of Americana like "The Old Rugged Cross," Stephen Foster's "Dixie," Franz von Suppe's "Light Cavalry Overture," the theme from The Twilight Zone, and (of course) "Louie Louie," to attack the piety of the Christian televangelists. Zappa even goes so far as to tie the Moral Majority's policies to what he sees as their Ku Klux Klan heritage by borrowing an unforgettable image from Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit":

If you ain't born again,

They wanna mess you up, screamin':

"No abortion, no-siree!"

"Life's too precious, can't you see!"

(What's that hangin' from a neighbor's tree?)

Why, it looks like 'colored folks' to me.

"Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk" is the shadow version of Elvis Presley's "An American Trilogy" (where songwriter Mickey Newbury included "Dixie," "Battle Hymn of the Republic" and "All My Trials"). Rather than nostalgically celebrate the country through a combined history of its songs, however, Zappa exposes the corruption he thinks those songs continue to hide.

I can't think of any other contemporary American composer who has reorganized his earlier work with the desire to tell a story about his country. Back in the late Seventies, in his 3-LP opus, Decade, Neil Young did something similar to Zappa. But on that album, Young drew for us a compelling picture of how he became the singer/songwriter we knew. On Understanding America, Zappa looks out into the nation itself rather inside himself to assess his own evolution as an artist. And though his judgments are as harsh as they are sometimes brutally funny, his views are anything but cynical about the electoral process. (At the end of "Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk," a live recording from the 1988 tour where he was registering people to vote, he encourages the audience to get out into the lobby at intermission and do so.) Greil Marcus, in his book, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music, once looked out at his country to examine its moral prerogatives through the music it created. "America is a trap: that its promises and dreams, all mixed up as love and politics and landscape, are too much to live up to and too much too escape," he wrote. Although the American political landscape is indeed deeply rooted in this Puritan heritage, Understanding America offers proof that America's best music, movies and paintings have always been brave attempts to refute it.

-- March 10/13

American Dreams & British Nightmares: Jim O'Brien's The Dressmaker (1988)

Thanks to The Beatles, Liverpool has become something of a tourist haven, apparently second only to the Tower of London for sightseers in England. Ironically, the city's history is hardly a cause for celebration. For while Liverpool spawned The Beatles, The Beatles ultimately wished to break free of this seaport locale. Even so, one could always hear the character of Liverpool in their songs, the sense that as things could always get worse, they would find ways to make things better. That goal is also a characteristic germane to the city, a quality Alistair Cooke once described as "cheerful pessimism." The cause of that "cheerful pessimism," though, came directly from Liverpool's disparate economic and cultural life which begins in the 18th Century, when the slave trade from Africa became mixed with the cotton market from North America. When abolition became law in 1807, slaves were not allowed to land in England, but since cotton was sent to manufacturing cities like Manchester and Birmingham by railroad, other immigrants made their way to the jobs.

By 1820, the dockyards and the Cotton Exchange attracted close to 160,000 Irish immigrants from across the channel to make the kind of money they couldn't make in Ireland. But the Irish would also become the despised in Liverpool and were the victims of both unrest and hopelessness. During the Depression years, with the merger of the Cunard and White Stripe shipping lines, the luxury liner traffic was being rerouted to Southhampton. This decision changed the industrial base of Liverpool diminishing their economic status. The only way that they could retain their former status was by becoming the anchor of the country's naval operations. But that change inadvertently created an adverse effect when relentless German air raids lead to massive destruction. By 1941, thousands were killed and the city was reduced to rubble. After the war, it took years to relocate over ten thousand persons.

|

| Liverpool in the Forties |